Abstract

Nesfatin-1, a pleiotropic peptide derived from the nucleobindin-2 precursor, exhibits widespread distribution in the central nervous system and peripheral tissues. It plays a critical role in regulating energy homeostasis. Its high concentration in the appetite control centers of the hypothalamus indicates that Nesfatin-1 is a potent anorexigenic peptide, which suppresses food intake through melanocortin-dependent but leptin-independent mechanisms. Its capacity to augment insulin secretion and regulate glucose metabolism by activating L-type calcium channels in pancreatic β-cells renders Nesfatin-1 a promising therapeutic target, particularly for type 2 diabetes. Nesfatin-1 has also been shown to be active in hypothalamic and limbic circuits associated with stress, anxiety, and behavioral responses. Levels of Nesfatin-1 exhibit fluctuations in response to acute and chronic stress conditions. Nesfatin-1 has been reported to increase arterial pressure via central oxytocinergic and melanocortinergic pathways in the cardiovascular system. At the peripheral level, it produces vasoconstrictive effects via eNOS inhibition. Although Nesfatin-1 has been demonstrated to possess anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties in experimental models, the findings from clinical studies are heterogeneous, and its potential as a biomarker remains uncertain. In summary, Nesfatin-1 is a significant molecule that has the potential to contribute to the development of novel treatment strategies for obesity, diabetes, neuropsychiatric disorders, and inflammatory processes. However, it is imperative to define its mechanisms with precision.

Keywords: hypothalamus, nesfatin-1, energy homeostasis, adipokines, obesity

Main Points

- Nesfatin-1 functions as a potent anorexigenic adipokine that plays a central role in energy homeostasis and modulates appetite regulation through leptin-independent pathways.

- Within adipose tissue, nesfatin-1 promotes lipolysis and reduces lipid accumulation, highlighting its importance in the pathophysiology of obesity and metabolic syndrome.

- Nesfatin-1 influences insulin secretion and glucose metabolism, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target in type 2 diabetes and related metabolic disorders.

- By modulating cardiovascular function—including central regulation of blood pressure and peripheral vascular tone—nesfatin-1 may contribute to the development of obesity-related hypertension.

- The diverse metabolic and neuroendocrine effects of nesfatin-1 position it as a promising biomarker and future therapeutic candidate for obesity, diabetes, and stress-associated metabolic dysfunctions.

Introduction

The intricate interplay among energy homeostasis, appetite regulation, glucose metabolism, and neuroendocrine signaling plays a pivotal role in maintaining physiological balance and in the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome. Nesfatin-1, a member of the anorexigenic peptide family, has emerged as a key regulatory molecule involved in these complex processes. Following its initial identification in hypothalamic nuclei by Oh-I et al. in 2006, nesfatin-1 rapidly gained attention as a critical factor in metabolic and neuroendocrine research, paving the way for extensive experimental and clinical investigations.1,2

Nesfatin-1 is an 82–amino acid peptide generated through the proteolytic processing of Nucleobindin-2 (NUCB2), a preproprotein composed of a 396–amino acid core region and a 24–amino acid signal peptide, resulting in a total length of 420 amino acids. During post-translational modification, NUCB2 is cleaved by peptidases into three biologically relevant fragments: nesfatin-1 (residues 1–82), nesfatin-2 (residues 85–163), and nesfatin-3 (residues 166–396). Among these cleavage products, nesfatin-1 has been identified as the primary biologically active fragment, exerting significant effects on energy balance, appetite suppression, and glucose metabolism.2 Furthermore, nesfatin-1, derived from the NUCB2 gene, is synthesized not only within the central nervous system but also in several peripheral tissues, including the gastric mucosa, adipose tissue, pancreas, and testes, indicating its pleiotropic physiological functions.3

The high density of nesfatin-1 expression in hypothalamic nuclei involved in appetite regulation, such as the arcuate nucleus (ARC), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), supraoptic nucleus (SON), and lateral hypothalamus, underscores its central role in food intake control and energy homeostasis. Notably, hypothalamic nesfatin-1 expression exhibits sensitivity to feeding and fasting states, suggesting a close association between nesfatin-1 signaling and metabolic status. In addition, nesfatin-1 concentrations in the gastric oxyntic mucosa are reported to be approximately 20-fold higher than those in the brain, emphasizing the importance of peripheral nesfatin-1 as a contributor to systemic energy regulation.4

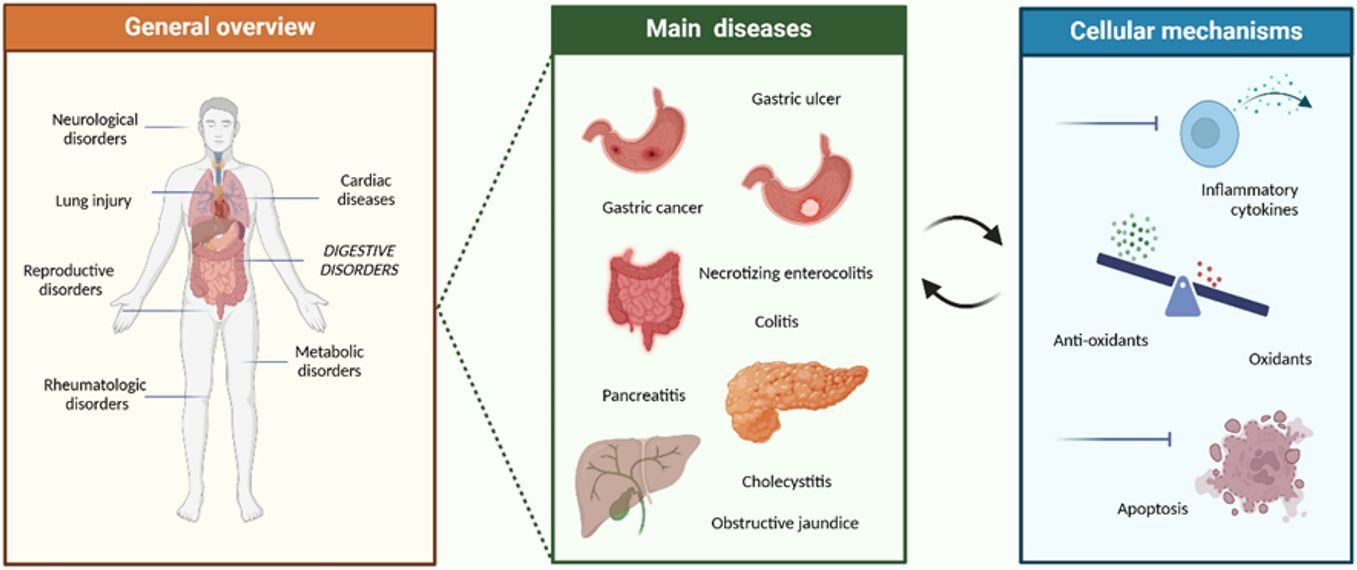

Recent studies have revealed that nesfatin-1 exerts a broader spectrum of biological effects than previously anticipated. Beyond its anorexigenic action, nesfatin-1 expression has been documented across multiple organ systems, implicating the peptide in diverse physiological and pathological conditions. As summarized in Figure 1, alterations in nesfatin-1 levels have been associated with a wide range of gastrointestinal and inflammatory disorders, including gastric ulcer, gastric cancer, colitis, necrotizing enterocolitis, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, and obstructive jaundice. At the cellular level, nesfatin-1 demonstrates cytoprotective properties, mediated through the inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine release, regulation of oxidative stress balance, and suppression of apoptosis. These mechanisms highlight nesfatin-1 as a potential therapeutic target for modulating inflammation, reducing tissue injury, and limiting disease progression.5

This review systematically and comprehensively addresses the biosynthesis and tissue distribution of nesfatin-1, its central and peripheral actions, and its involvement in metabolic and neuroendocrine regulation. Additionally, current clinical findings, controversial issues within the existing literature, and future research directions are critically discussed. In this context, nesfatin-1 is regarded as a pivotal neuroendocrine mediator of energy balance and is considered a promising candidate for the development of novel therapeutic strategies targeting metabolic and inflammatory diseases.

General Information

Nesfatin-1 and the structures that secret

In 2006, Oh-1 and colleagues discovered nesfatin-1, a hormone secreted from the hypothalamic nucleus that regulates appetite. In this study, it was reported that food intake was inhibited by nesfatin-1 even in obese mice lacking the leptin gene.2 Consequently, the potential of nesfatin-1 has generated optimism for the treatment of obese individuals with leptin gene mutations. The release of nesfatin-1 is known to decrease during periods of hunger, suggesting a regulatory role in energy balance.6

Nesfatin-1 and its precursor peptide have been reported to be widely and abundantly distributed throughout the central nervous system, indicating a multifunctional neuroregulatory role. The presence of this peptide has been clearly demonstrated in key hypothalamic nuclei critically involved in energy balance, stress response, and neuroendocrine regulation, including the arcuate nucleus (ARC), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), supraoptic nucleus (SON), and lateral hypothalamus, as well as in the pituitary gland, highlighting its potential influence on hypothalamic–pituitary axis activity. Furthermore, nesfatin-1 expression has been identified in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), a major integrative center within the brainstem responsible for autonomic and visceral signal processing, in addition to multiple nuclei of the forebrain, midbrain, and the central amygdaloid complex, suggesting its involvement in emotional regulation, stress-related behaviors, and autonomic control.4

In addition, accumulating evidence indicates that nesfatin-1 is expressed in extra-hypothalamic and lower brain regions, including the cerebellum and ventrolateral medulla, as well as in the preganglionic neurons of the sympathetic spinal cord at the thoracolumbar level and the parasympathetic spinal cord at the sacral level in experimental rat models.7 This widespread neuroanatomical distribution strongly supports the notion that nesfatin-1 participates not only in metabolic regulation but also in autonomic nervous system modulation and integrative neurophysiological processes.7

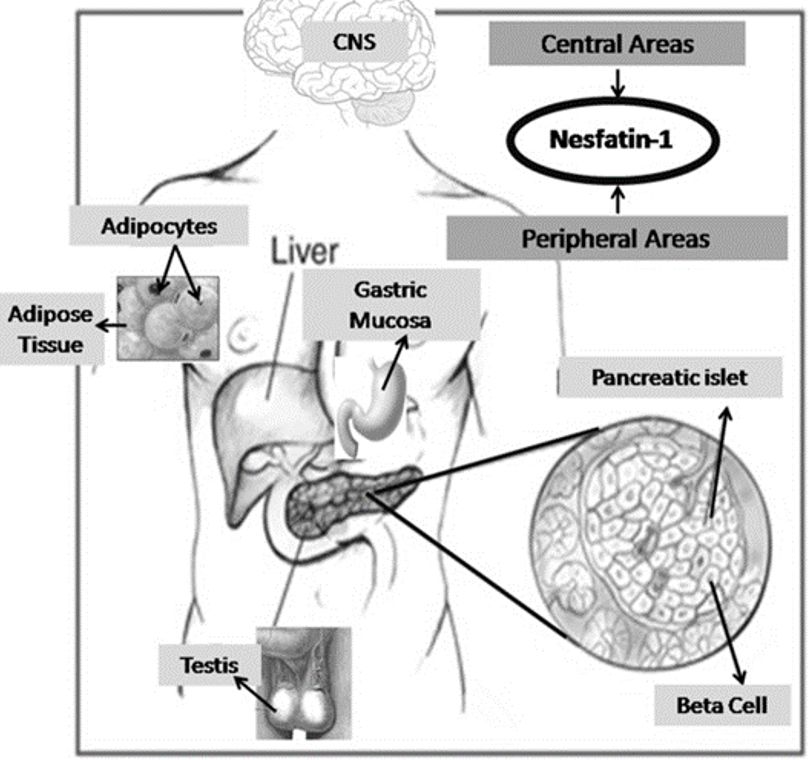

A multitude of studies have reported the secretion of nesfatin-1 by the central nervous system (CNS) as well as by peripheral tissues, including but not limited to adipose tissue, gastric mucosa, endocrine pancreatic beta cells, and testes.4 The level of this substance in the gastric oxyntic mucosa was found to be 20 times higher than in the brain (Figure 2).8

The Effects of Nesfatin-1

Effect on food intake

Nesfatin-1, whose mRNA and protein expression levels are markedly elevated in key central regions such as the hypothalamic nuclei and brainstem, has been closely linked to the regulation of metabolic processes and the suppression of food intake.9 The presence of nesfatin-1 in multiple brain regions involved in feeding behavior and emotional regulation, including the limbic system, hypothalamus, pons, and medullary nuclei, further supports its regulatory role in appetite control and energy balance.

The influence of energy status alterations associated with acute or chronic malnutrition on nesfatin-1 mRNA and protein expression levels in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and supraoptic nucleus (SON) has been well documented, highlighting its sensitivity to nutritional cues. Recent findings have demonstrated a positive correlation between increased levels of anorexigenic factors, such as cholecystokinin and melanocyte-stimulating hormone, and a subsequent upregulation of NUCB2 mRNA expression.10 This upregulation has been shown to activate nesfatin-1–immunopositive neurons within both the hypothalamus and brainstem, indicating a coordinated neuroendocrine response to satiety signals.

Notably, nesfatin-1 has been reported to modulate both food and water intake through a leptin-independent but melanocortin-dependent signaling pathway, suggesting that it operates via distinct neuroendocrine circuits separate from classical leptin-mediated mechanisms.11

In dose-dependent experimental studies conducted in male Wistar rats, intracerebroventricular administration of nesfatin-1 into the third ventricle resulted in a significant reduction in both food intake and body weight.7 These findings have been consistently replicated across different laboratories and species, including mice, rats, and goldfish, underscoring the robust and evolutionarily conserved anorexigenic effect of nesfatin-1.

Low-dose nesfatin-1 administration (5–20 pmol) into the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles, as well as the cisterna magna and specific hypothalamic regions such as the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), and dorsal vagal complex (DVC), has been shown to induce pronounced anorexigenic effects. These low-dose applications were found to suppress food intake for prolonged durations (6–48 hours), particularly during the dark phase, when feeding activity is normally increased. In contrast, higher-dose injections (25–80 pmol) not only enhanced the anorexigenic response but also elicited anxiety-like behaviors, indicating a dose-dependent divergence in central effects.

Microinjection studies have further demonstrated that the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) serves as the primary hypothalamic site mediating the anorexigenic action of nesfatin-1, highlighting its central role in appetite suppression.2,7 Additionally, pharmacological blockade of endogenous nesfatin-1 signaling using neutralizing antibodies or antisense oligonucleotides has been shown to increase food intake and promote weight gain, providing functional evidence for its physiological relevance.

Consistent with these observations, NUCB2 mRNA and protein levels in the PVN and SON regions have been reported to decrease during fasting or starvation and to return to baseline levels upon refeeding, further supporting the role of nesfatin-1 as a nutritional status–responsive regulator of energy homeostasis.12,13

Nesfatin-1, a hormone whose mRNA and protein levels are elevated in regions such as the hypothalamic nucleus and brain stem, has been linked to the regulation of metabolism and the suppression of food intake.9 The presence of Nesfatin-1 in regions such as the limbic system, hypothalamus, pons, and medullary nucleus suggests that it plays a regulatory role in relation to food intake. The impact of energy shifts associated with acute or chronic malnutrition on Nesfatin-1 mRNA and protein levels in the hypothalamic PVN and SON is well-documented. Recent findings have indicated a correlation between the increase in certain substances that inhibit food consumption—such as cholecystokinin and melanocyte-stimulating hormone—and the subsequent increase in NUCB2 mRNA expression levels.10 This increase, in turn, has been observed to lead to the activation of nesfatin-1-immunopositive neurons located within the hypothalamus and brain stem. Nesfatin-1 has been found to affect water and food intake via a leptin-independent, melanocortin-dependent system.11

In dose-dependent experiments conducted on male Wistar rats, it was found that intracerebroventricular injections into the third ventricle significantly reduced food intake and body weight.7 This finding has been replicated and confirmed by different research groups in various animal models, including mice, rats, and goldfish. The administration of low-dose injections (5–20 pmol) into the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles, the cisterna magna, and the hypothalamic nuclei PVN, lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), and dorsal vagal complex (DVC) regions has been reported to produce anorexigenic effects. Low-dose applications have been shown to reduce food intake for an extended period (6–48 hours) during the dark phase, while high-dose injections (25–80 pmol) have been observed to induce anxiety-like behaviors in addition to the anorexigenic effect. The results of microinjection studies have demonstrated that the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) is the primary hypothalamic center responsible for the anorexigenic effect of nesfatin-1.2,7 In addition, the obstruction of endogenous nesfatin-1 signaling through the utilization of antibodies or antisense oligonucleotides has been observed to result in augmented feeding and weight gain. It has been reported that levels of NUCB2 mRNA and protein decrease in the PVN and SON regions during starvation and return to normal levels upon refeeding.12,13

In addition to its effects on the central nervous system, it has been demonstrated that nesfatin-1 also regulates food intake at the peripheral level. Nesfatin-1 has been detected in rodents and human plasma, and its potential sources include subcutaneous adipose tissue, endocrine cells of the gastric mucosa, intestines, and pancreatic β-cells. Plasma levels have been documented to decline during periods of fasting and return to normal following refeeding.14 The continuous peripheral infusion led to a reduction in food intake, while the high-dose intraperitoneal administration suppressed feeding during the dark phase.15 The durability of this anorexigenic effect in obese db/db mice, which carry a leptin receptor mutation, suggests that nesfatin-1 operates through a leptin-independent mechanism. A study of structural fragments revealed that the anorexigenic effect of nesfatin-1 originates from the central portion of the protein, specifically the amino acid sequence spanning residues 24–53.4,16 In contrast, the N- and C-terminal fragments were found to be ineffective. Following peripheral administration, nesfatin-1 was reported to cross the blood-brain barrier and directly affect feeding centers. Additionally, it was reported to exert anorexigenic effects via indirect mechanisms through activation of vagal afferents and stimulation of POMC and CART neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) region.7,17

In summary, nesfatin-1 is a potent and multifunctional anorexigenic peptide that suppresses food intake through both central and peripheral regulatory mechanisms. These mechanisms include leptin-independent yet melanocortin-dependent signaling pathways, indicating that nesfatin-1 operates via distinct neuroendocrine circuits beyond classical satiety hormones. Its marked sensitivity to the hunger–satiety cycle further underscores its critical role in the fine-tuned regulation of energy homeostasis, positioning nesfatin-1 as a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of obesity and related metabolic disorders.

Recent experimental studies have demonstrated that nesfatin-1 modulates the activity of gastric satiety-sensitive neurons and regulates gastric motility via melanocortin signaling within the central nucleus of the amygdala, highlighting a functional link between emotional processing centers and gastrointestinal control. Furthermore, nesfatin-1 has been characterized as an inhibitory neurotransmitter that influences gastric motor function through its actions on key hypothalamic regions, including the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA).

Despite these advances, the precise neuroanatomical pathways, receptor mechanisms, and context-dependent effects through which nesfatin-1 regulates feeding behavior remain incompletely understood. Therefore, further comprehensive experimental and translational studies are required to fully elucidate the role of nesfatin-1 in appetite control, gut–brain communication, and long-term energy balance regulation.7

Effect on the nervous system

Evidence has been presented demonstrating the presence of neurons expressing NUCB2, the precursor peptide of Nesfatin-1, in multiple regions of the brain. A subset of NUCB2-positive neurons situated within the parvocellular region of the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVH) have been observed to express the melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R).18 These neurons have been shown to receive signals from α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and agouti-related protein (AgRP) fibers. It has been documented that α-MSH has the capacity to enhance the synthesis and secretion of nesfatin-1. A particular study revealed that NUCB2-expressing neurons in the PVH (pPVH) induce anorexigenic effects through the secretion of nesfatin-1.19 However, the precise mechanism of action of nesfatin-1 remains to be elucidated.15

The central release of nesfatin-1 is subject to fluctuations in response to alterations in metabolic status. A multitude of studies have demonstrated that following a 24-hour fasting period, there is a decrease in the transcription and translation levels of nesfatin-1 in both the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVH) and the supraoptic nucleus (SON) regions. In the SON region, a notable increase in nesfatin-1 synthesis and release is observed following refeeding after a 24-hour period of fasting. Peripheral injection of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and serotonin 5-HT receptor antagonists, which have anorexigenic effects, has been demonstrated to increase hypothalamic nesfatin-1 release in rodent models. The administration of ghrelin, an orexigenic hormone, at orexigenic doses has been demonstrated to increase the activity of nesfatin-1-producing neurons located in the arcuate nucleus (ARC). Furthermore, peripheral injection of cholecystokinin (CCK), a satiety peptide, has been shown to increase the activity of neurons responsible for nesfatin-1 release in both the parvocellular region of the paraventricular nucleus (pPVN) and the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) regions. These findings suggest that nesfatin-1 interacts with various feeding peptides involved in satiety signaling.14 Conversely, the sensation of hunger is believed to be modulated by peripheral metabolic signaling molecules, including leptin and ghrelin. The effects of ghrelin on the ARC have been shown to result in a decrease in the activity of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons and an increase in the activity of agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons.15 In the 2006 study, the author and colleagues proposed that hunger reduces the activity of NUCB2-expressing neurons located in the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVH) via melanocortin signaling pathways.2

Its effect on stress and anxiety

It is widely believed that nesfatin-1 plays a regulatory role in stress-related responses physiological and may contribute to the development of stress-induced anorexia, an effect that is thought to arise from the activation of NUCB2-secreting neurons located in the posterior paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (pPVH).9 This region is known to be critically involved in integrating neuroendocrine and autonomic responses to stress, supporting the proposed role of nesfatin-1 in stress adaptation.

Magnocellular neurons, which are prominently distributed in the supraoptic nucleus (SON) and posterior pituitary projections, are primarily responsible for the regulation of water and electrolyte balance through the secretion of neurohormones such as vasopressin and oxytocin. It is therefore plausible that alterations in water balance may indirectly influence the regulatory functions of NUCB2-expressing neurons within this region, suggesting a potential interaction between fluid homeostasis and nesfatin-1–mediated stress responses.

Unexpectedly, experimental evidence indicates that classical metabolic regulators such as fasting and melanocortin signaling do not significantly affect NUCB2-expressing neurons located in the medial paraventricular hypothalamus (mPVH), SON, arcuate nucleus (ARH), lateral hypothalamus/intercalated zone (LHA/ZI), and nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS).19 This lack of responsiveness to well-established metabolic cues highlights a significant gap in current knowledge and suggests that the precise physiological function of NUCB2 neurons in these regions remains poorly understood, warranting further targeted investigation.

In acute stress situations, an increase in nesfatin-1 levels is observed in the central nervous system; however, this increase is not reflected in plasma concentrations. However, recent studies have demonstrated that chronic stress exposure can increase plasma levels of nesfatin-1.20,21

A multitude of studies have demonstrated that nesfatin-1 may exert specific effects on anxiety. Recent observations have indicated that the administration of nesfatin-1 to the central nervous system results in an augmentation of anxiety-like behaviors. Furthermore, the study examined the relationship between variations in serum nesfatin-1 levels and alterations in eating behaviors observed in depressed individuals. In this context, one study reported that serum nesfatin-1 levels in individuals diagnosed with depression were significantly higher than in the healthy control group.22 These findings suggest that nesfatin-1 may potentially play a role in regulating anxiety-like behaviors.23,24

Effect on the endocrine system

The influence of substances secreted in brain regions associated with nesfatin-1 on nutritional behavior, neuroendocrine regulation, autonomic control, visceral functions, sleep, mood, and pain is a subject of considerable interest. Consequently, it is plausible that nesfatin-1 may be associated with behaviors that extend beyond the realm of nutritional behavior. The significant presence of nesfatin-1 in endocrine tissues suggests a potential role in hormone secretion. Its presence in the stomach suggests a potential yet to be elucidated effect on food intake. Additionally, the presence of nesfatin-1 in the pancreas suggests a potential role in insulin- and glucagon-mediated glucose metabolism. The presence of nesfatin-1 in peripheral tissues corroborates its critical function in regulating energy homeostasis, neuroendocrine functions, and hypothalamic anorexic signaling. Additionally, the detection of nesfatin-1 in plasma is widely accepted as substantiating evidence for its hormonal activity.25,26

Subsequent to the central injection of Nesfatin-1, there was an increase in circulating LH and FSH hormone levels in adolescent female rats, both in the ad libitum fed and fasted groups. However, this effect was not observed in adult female rats. These findings suggest a potential role for Nesfatin in the developmental process of adolescence.27

A study was conducted to examine the effects of nesfatin-1 on testosterone release. The results demonstrated that central administration of this peptide caused significant increases in plasma follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and testosterone levels in rats. However, these increases did not result in a significant change in plasma gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) levels compared to the control group. These findings demonstrated for the first time that central injection of nesfatin-1 can regulate FSH, LH, and testosterone levels in males via the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (HPGA).28

In accordance with the potential effects of Nesfatin-1 on the endocrine system, it has been proposed that increases or decreases in serum levels could be evaluated as biomarkers for certain diseases. In order to provide support for this hypothesis, an examination of serum nesfatin-1 levels was conducted across various patient groups. However, two of these studies reported conflicting results: One study suggested that low nesfatin-1 levels may play a role in the pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS),29 while the other reported that high nesfatin-1 levels may be associated with PCOS.30 The observed discrepancy between these results is hypothesized to stem from differences in study methodology, sample characteristics, experimental conditions, and genetic differences. Consequently, the identification of potential polymorphic regions in the nesfatin-1 gene may facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of this peptide’s role in the development of various diseases.

Effect on diabetes mellitus

A comprehensive evaluation of the relevant literature has reported the protective and glucose-lowering effects of nesfatin-1 under hyperglycemic conditions. Intravenous administration of nesfatin-1 has been shown to induce a marked reduction in plasma glucose levels in hyperglycemic db/db mice, a widely accepted experimental model of type 2 diabetes mellitus.31 The available data indicate that this hypoglycemic effect is primarily mediated through peripheral mechanisms and displays time-dependent and dose-dependent characteristics, as well as a partial association with circulating insulin levels.

Conversely, the absence of a comparable glucose-lowering effect of nesfatin-1 in a streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes model, which is characterized by severe pancreatic β-cell damage, suggests that this mechanism may not rely exclusively on direct insulin secretion. These findings point to the involvement of insulin-independent or insulin-sensitizing pathways, although the precise molecular mechanisms underlying this effect remain incompletely elucidated.

In the same experimental framework, intracerebroventricular administration of nesfatin-1 in db/db mice resulted in a significant suppression of food intake without producing a corresponding reduction in blood glucose levels, indicating that the antihyperglycemic effect of nesfatin-1 is independent of its central anorexigenic action.32

Collectively, the appetite-suppressing (anorexigenic) and glucose-lowering (antihyperglycemic) properties of nesfatin-1 highlight its dual regulatory role in energy intake and glucose metabolism, respectively.33 These observations strongly suggest that nesfatin-1 exerts a multifaceted influence on the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. Accordingly, nesfatin-1 has been proposed as a potential therapeutic target in the management of metabolic disorders, particularly type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity.

Moreover, experimental evidence suggests that nesfatin-1 may act as an antidiabetic agent by promoting insulin release and by enhancing insulin sensitivity, potentially through the facilitation of free fatty acid utilization and modulation of insulin resistance pathways.34,35 Nevertheless, despite these promising findings, the exact physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms through which nesfatin-1 regulates glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism remain to be fully clarified, underscoring the need for further mechanistic and translational studies.35

Effect on the immune system

A study demonstrated that nesfatin-1 exerts significant anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects in rats with a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) model. In this experimental model, increases in tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels were observed in brain tissue, while a significant decrease in antioxidant enzyme levels was detected.36 Recent studies have indicated a potential correlation between decreased serum nesfatin-1 levels and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), suggesting a possible anti-inflammatory response as a contributing factor.37 In addition, the results of a study conducted on individuals with emphysema-type chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) suggest that nesfatin-1 may serve as a novel biomarker associated with systemic inflammation.38 This finding indicates that nesfatin-1 may potentially function as an inflammatory factor in this particular patient population. While these findings highlight the role of nesfatin-1 in regulating inflammatory responses, further research is needed to fully elucidate this mechanism.

Effect on the cardiovascular system

A multitude of studies have underscored the pivotal function of nesfatin-1 in modulating cardiovascular stress responses through the central nervous system. Specifically, it has been demonstrated that the intracerebrospinal injection of this peptide results in a significant increase in arterial blood pressure.9,39 In experimental models employing melanocortin and oxytocin receptor antagonists, it has been observed that both the appetite-suppressing effects and the blood pressure-raising effects of nesfatin-1 are eliminated. Recent findings have revealed that nesfatin-1, which is localized in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) in conjunction with oxytocin, has been shown to stimulate oxytocin release through the neuronal depolarization mechanism. In addition, it has been reported that nesfatin-1 can activate melanocortin signaling pathways via oxytocin. In light of these findings, it has been proposed that the hypertensive effects of nesfatin-1 may be associated with the central oxytocinergic system or the melanocortin pathway. However, the question of whether these two systems are activated simultaneously or sequentially, and which molecular mediators are involved in this process, remains unresolved.14,25

Intravenous administration of nesfatin-1 has been demonstrated to significantly inhibit nitric oxide (NO) production, thereby inducing a vasoconstrictive response and consequently leading to an increase in systemic arterial blood pressure.40 This effect underscores the role of nesfatin-1 as an active modulator of vascular tone and cardiovascular regulation.

In a particular experimental study, peripheral administration of nesfatin-1 was shown to result in a marked reduction in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression, an effect that was especially pronounced in rats subjected to chronic stress exposure.5 The stress-dependent enhancement of this response suggests a potential interaction between nesfatin-1 signaling and stress-related neurovascular pathways. Collectively, these findings indicate that the hypertensive effect of peripheral nesfatin-1 is mediated, at least in part, through the suppression of the eNOS–NO signaling pathway, ultimately promoting vasoconstriction as the primary underlying mechanism.41,42 This mechanism positions nesfatin-1 as a potential link between metabolic regulation, stress physiology, and cardiovascular dysfunction.

Intravenous administration of nesfatin-1 has been demonstrated to inhibit nitric oxide (NO) production, thereby inducing a vasoconstrictive effect and, consequently, an increase in systemic blood pressure.40 In a particular study, the administration of peripheral nesfatin-1 was found to result in a significant reduction in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) levels, particularly in rats exposed to chronic stress.5 These findings suggest that the effect of peripheral nesfatin-1 on blood pressure occurs via eNOS and NO and likely manifests through the vasoconstriction mechanism.41,42

Effect on l-type calcium channels

A study employing primary hypothalamic neuronal cell cultures in rats has demonstrated that nesfatin-1 exhibits pharmacological characteristics consistent with G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR)–mediated signaling pathways. Specifically, the findings revealed that nesfatin-1 induces a significant increase in intracellular calcium (Ca²+) concentration, indicating the activation of calcium-dependent signaling mechanisms. Moreover, the observation that selective inhibition of L-, P-, and Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel subunits markedly attenuated the nesfatin-1–induced calcium response provides strong evidence that these calcium channel subtypes are directly or indirectly activated by nesfatin-1. These results further support the hypothesis that nesfatin-1 exerts its biological effects through GPCR-linked calcium signaling cascades.

In addition, this study demonstrated the neuronal expression of nesfatin-1 in both the hypothalamus and brainstem, highlighting its relevance in central neuroendocrine and autonomic regulation.43 Furthermore, complementary investigations using hypothalamic neural cell culture models have consistently shown that nesfatin-1 facilitates intracellular calcium influx via GPCR-dependent mechanisms, reinforcing the concept that calcium signaling constitutes a key downstream pathway in nesfatin-1–mediated neuronal effects.44,45

A separate study indicated that nesfatin-1 enhances insulin secretion by activating L-type calcium channels in pancreatic islet beta cells. The increase in intracellular calcium is not dependent on protein kinase A and phospholipase A2. Recent findings have indicated a correlation between the increase in intracellular calcium levels and glucose levels. Specifically, following a meal, an increase in plasma glucose levels has been observed to result in elevated glucose-stimulated intracellular calcium levels in pancreatic islet beta cells, thereby inducing increased insulin secretion.46

In a separate study, it was discovered that long-term administration of nesfatin-1 to the peripheral region can increase the expression level of the α1c subunit protein in cardiac L-type calcium channels, particularly under chronic stress conditions. It has been hypothesized that the effect of nesfatin-1 on the heart may result in substantial damage to cardiomyocytes.47

Result

Nesfatin-1 is a pleiotropic and highly conserved peptide that exerts multifaceted regulatory effects on energy homeostasis, appetite regulation, glucose metabolism, neuroendocrine control, cardiovascular responses, inflammatory pathways, and stress-related physiological mechanisms. This biologically active molecule is derived from the post-translational cleavage of the NUCB2 precursor protein and is widely expressed in both central nervous system structures and diverse peripheral tissues, underscoring its systemic regulatory capacity.

Nesfatin-1 plays a crucial role as a satiety signal and contributes to the integrated regulation of whole-body physiological functions. Its prominent localization in key hypothalamic appetite- and energy-regulating centers, including the arcuate nucleus (ARC), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), supraoptic nucleus (SON), and lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), provides compelling evidence for its central involvement in the neuroendocrine control of energy balance and feeding behavior.

In this context, nesfatin-1 is regarded as a pivotal mediator in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis, functioning at the intersection of central and peripheral signaling pathways. Moreover, its interaction with stress-responsive neuroendocrine circuits highlights its role in coordinating adaptive physiological responses to environmental and metabolic stressors, further supporting its relevance in health and disease.

The extant literature suggests that nesfatin-1 exerts potent anorexigenic effects at both central and peripheral levels through mechanisms that are both leptin-independent and melanocortin-dependent. This property facilitates the evaluation of nesfatin-1 as a potential therapeutic target, particularly in the context of obesity management, where leptin resistance is frequently observed. Moreover, the finding that nesfatin-1 increases insulin secretion and modulates glucose metabolism by activating L-type calcium channels in pancreatic β-cells is noteworthy for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. However, the literature contains conflicting findings regarding the insulin-dependence of its effects on glycemic regulation, indicating that the underlying mechanism of this molecule has not yet been fully elucidated.

The observed activity of Nesfatin-1 in neural circuits associated with stress, anxiety, and behavioral responses suggests the potential for this peptide to be linked to neuropsychiatric processes. The increases observed at the central level under acute stress conditions and elevated plasma concentrations under chronic stress conditions suggest that nesfatin-1 plays a regulatory role in stress adaptation mechanisms. However, the observation that nesfatin-1 administration can induce anxiety-like behaviors underscores the necessity for prudence in interpreting the neuropsychiatric effects of this molecule and the imperative for more exhaustive investigation of its underlying mechanisms.

Research conducted on the cardiovascular system has demonstrated that nesfatin-1 has the capacity to elevate arterial blood pressure through both central and peripheral mechanisms. This hypertensive effect, reported to be associated with oxytocinergic and melanocortinergic pathways, is considered to potentially pose a limitation, particularly for individuals at cardiovascular risk. Another mechanism that should be carefully considered in clinical practice is vasoconstrictive effects arising from peripheral inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and decreased nitric oxide production. These findings underscore the importance of conducting a comprehensive investigation into the effects of nesfatin-1 on cardiovascular homeostasis, taking into account both its therapeutic potential and its potential risks.

In experimental studies conducted within the context of the immune system, nesfatin-1 has been demonstrated to exert notable anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects, supporting the hypothesis that this peptide possesses significant cytoprotective properties. These experimental findings suggest that nesfatin-1 may play a regulatory role in immune responses and inflammation-associated tissue injury.

However, results obtained from human studies have been highly heterogeneous and, in some cases, contradictory, indicating that the clinical applicability of nesfatin-1 as a reliable inflammation biomarker has not yet been clearly established. Moreover, inconsistent and disease-specific alterations in circulating nesfatin-1 levels reported in conditions such as epilepsy, polycystic ovary syndrome, and various metabolic disorders further limit its current reliability as a clinical biomarker.

Consequently, there is a clear need for advanced, standardized, and large-scale clinical investigations employing uniform measurement techniques, well-defined patient populations, and longitudinal study designs to elucidate the precise role of nesfatin-1 in immunological and metabolic processes and to determine its potential utility as a clinically meaningful biomarker.

In summary, nesfatin-1 is a neuropeptide that exerts a multifaceted role in physiological processes, demonstrating a broad spectrum of effects and high therapeutic potential. However, the fact that most of the extant studies are based on experimental animal models, while human data are limited, conflicting, and methodologically heterogeneous, necessitates careful evaluation of inferences regarding clinical applications. It is imperative that future research prioritize elucidating the detailed molecular mechanisms of action of nesfatin-1, characterizing its receptor-level interactions, determining dose-response relationships, and assessing long-term clinical safety.

In summary, nesfatin-1 is a key integrative neuroendocrine molecule involved in the coordinated regulation of energy balance, glucose metabolism, appetite control, and neuroendocrine signaling pathways. Accumulating experimental and clinical evidence suggests that nesfatin-1 holds significant promise as a biomarker and potential therapeutic target in a broad spectrum of clinical conditions, including obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, neuropsychiatric disorders, cardiovascular dysfunctions, and inflammatory diseases.

Despite these promising findings, the precise mechanisms of action, receptor pathways, and tissue-specific effects of nesfatin-1 remain incompletely understood. Therefore, the successful translation of its biological potential into clinical practice requires large-scale, well-designed, and long-term human studies, with particular emphasis on standardized measurement methods, population heterogeneity, and longitudinal outcome assessments. Clarifying these aspects will be essential for determining the clinical utility of nesfatin-1–based diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all colleagues who contributed to this review by providing data support, assisting with technical processes, aiding in literature search, or offering critical feedback, but who did not meet the authorship criteria. As their contributions did not reach the level required for authorship, they are not listed among the authors of this manuscript.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Kleiboeker B, Lodhi IJ. Peroxisomal regulation of energy homeostasis: effect on obesity and related metabolic disorders. Mol Metab. 2022;65:101577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101577

- Oh-I S, Shimizu H, Satoh T, et al. Identification of nesfatin-1 as a satiety molecule in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2006;443:709-712. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05162

- Kras K, Muszyński S, Tomaszewska E, Arciszewski MB. Minireview: peripheral nesfatin-1 in regulation of the gut activity-15 years since the discovery. Animals (Basel). 2022;12:101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12010101

- Yurtseven DG, Minbay Z, Eyigör Ö. Besin alımının kontrolündeki anoreksijenik peptit: nesfatin-1. J Uludag Univ Med Fac. 2018;44(2):135-142. https://doi.org/10.32708/uutfd.447361

- Damian-Buda AC, Matei DM, Ciobanu L, et al. Nesfatin-1: a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in digestive diseases. Biomedicines. 2024;12:1913. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081913

- Erkaya Z. Investigation of the possible effect of mu opioid receptors on the expression of some orexigenic and anorexigenic molecules in the hypothalamus in adult rats [master’s thesis]. Konya, Türkiye: Necmettin Erbakan University; 2024.

- Yurtseven DG. Immunohistochemical investigation of glutamatergic system effects on nesfatin neurons [master’s thesis]. Konya, Türkiye: Selçuk University; 2018.

- Aydın B. The investigation of the mediation of central cholinergic system in nesfatin-1 evoked cardivascular effects [master’s thesis]. Bursa, Turkey: Bursa Uludağ University; 2017.

- Ayada C, Toru Ü, Korkut Y. Nesfatin-1 and its effects on different systems. Hippokratia. 2015;19(1):4-10.

- Stengel A, Taché Y. Role of brain NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in the regulation of food intake. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:6955-6959. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161281939131127125735

- Dore R, Krotenko R, Reising JP, et al. Nesfatin-1 decreases the motivational and rewarding value of food. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:1645-1655. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-0682-3

- Moreau JM, Ciriello J. Nesfatin-1 induces Fos expression and elicits dipsogenic responses in subfornical organ. Behav Brain Res. 2013;250:343-350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.036

- Stengel A. Nesfatin-1 - More than a food intake regulatory peptide. Peptides. 2015;72:175-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2015.06.002

- Ramanjaneya M, Chen J, Brown JE, et al. Identification of nesfatin-1 in human and murine adipose tissue: a novel depot-specific adipokine with increased levels in obesity. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3169-3180. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2009-1358

- Dore R, Levata L, Lehnert H, Schulz C. Nesfatin-1: functions and physiology of a novel regulatory peptide. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R45-R65. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-16-0361

- Shimizu H, Oh-I S, Okada S, Mori M. Nesfatin-1: an overview and future clinical application. Endocr J. 2009;56:537-543. https://doi.org/10.1507/endocrj.k09e-117

- Baccari MC, Vannucchi MG, Idrizaj E. The possible involvement of glucagon-like peptide-2 in the regulation of food intake through the gut-brain axis. Nutrients. 2024;16:3069. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16183069

- Schalla MA, Stengel A. Current understanding of the role of nesfatin-1. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2:1188-1206. https://doi.org/10.1210/js.2018-00246

- Cowley MA, Grove KL. To be or NUCB2, is nesfatin the answer? Cell Metab. 2006;4:421-422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2006.11.001

- Xu YY, Ge JF, Qin G, et al. Acute, but not chronic, stress increased the plasma concentration and hypothalamic mRNA expression of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in rats. Neuropeptides. 2015;54:47-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npep.2015.08.003

- Goebel M, Stengel A, Wang L, Taché Y. Restraint stress activates nesfatin-1-immunoreactive brain nuclei in rats. Brain Res. 2009;1300:114-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.082

- Xiao MM, Li JB, Jiang LL, Shao H, Wang BL. Plasma nesfatin-1 level is associated with severity of depression in Chinese depressive patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1672-4

- Algül S, Dinçer E. The essential role of nesfatin-1 as a biological signal on the body systems. Kastamonu Med J. 2021;1(4):113-118. https://doi.org/10.51271/KMJ-0028

- Ari M, Ozturk OH, Bez Y, Oktar S, Erduran D. High plasma nesfatin-1 level in patients with major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:497-500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.12.004

- García-Galiano D, Navarro VM, Gaytan F, Tena-Sempere M. Expanding roles of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in neuroendocrine regulation. J Mol Endocrinol. 2010;45:281-290. https://doi.org/10.1677/JME-10-0059

- Bonnet MS, Pecchi E, Trouslard J, Jean A, Dallaporta M, Troadec JD. Central nesfatin-1-expressing neurons are sensitive to peripheral inflammatory stimulus. J Neuroinflammation. 2009;6:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-6-27

- Gao X, Zhang K, Song M, et al. Role of nesfatin-1 in the reproductive axis of male rat. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32877. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32877

- Yalçın E, Güvenç G, Altınbaş B, Özyurt E, Yalçın M. Nesfatin’in erkek sıçanlarda hipotalamo-hipofizer-gonadal aks üzerine etkileri. In: 2nd International Mardin Artuklu Scientific Research Congress, Applied Sciences Full Text Book. Mardin, Türkiye; 2019: 129.

- Deniz R, Gurates B, Aydin S, et al. Nesfatin-1 and other hormone alterations in polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrine. 2012;42:694-699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-012-9638-7

- Ademoglu EN, Gorar S, Carlıoglu A, et al. Plasma nesfatin-1 levels are increased in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014;37:715-719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-014-0089-2

- Tekin T, Cicek B, Konyaligil N. Regulatory peptide nesfatin-1 and its relationship with metabolic syndrome. Eurasian J Med. 2019;51:280-284. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurasianjmed.2019.18420

- Prinz P, Teuffel P, Lembke V, et al. Nesfatin-130-59 injected intracerebroventricularly differentially affects food intake microstructure in rats under normal weight and diet-induced obese conditions. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00422

- Dong J, Xu H, Xu H, et al. Nesfatin-1 stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase in STZ-induced type 2 diabetic mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83397. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083397

- Riva M, Nitert MD, Voss U, et al. Nesfatin-1 stimulates glucagon and insulin secretion and beta cell NUCB2 is reduced in human type 2 diabetic subjects. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;346:393-405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-011-1268-5

- Kadim BM, Hassan EA. Nesfatin-1 - as a diagnosis regulatory peptide in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2022;21:1369-1375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-022-01070-8

- Tang CH, Fu XJ, Xu XL, Wei XJ, Pan HS. The anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of nesfatin-1 in the traumatic rat brain. Peptides. 2012;36:39-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2012.04.014

- Shen P, Han Y, Cai B, Wang Y. Decreased levels of serum nesfatin-1 in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breath. 2015;19:515-522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-014-1039-0

- Leivo-Korpela S, Lehtimäki L, Hämälainen M, et al. Adipokines NUCB2/nesfatin-1 and visfatin as novel inflammatory factors in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:232167. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/232167

- Imbrogno S, Angelone T, Cerra MC. Nesfatin-1 and the cardiovascular system: central and pheripheral actions and cardioprotection. Curr Drug Targets. 2015;16:877-883. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450116666150408101431

- Ayada C, Turgut G, Turgut S, Güçlü Z. The effect of chronic peripheral nesfatin-1 application on blood pressure in normal and chronic restraint stressed rats: related with circulating level of blood pressure regulators. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2015;34:81-88. https://doi.org/10.4149/gpb_2014032

- Mori Y, Shimizu H, Kushima H, et al. Nesfatin-1 suppresses peripheral arterial remodeling without elevating blood pressure in mice. Endocr Connect. 2019;8:536-546. https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-19-0120

- Yamawaki H, Takahashi M, Mukohda M, Morita T, Okada M, Hara Y. A novel adipocytokine, nesfatin-1 modulates peripheral arterial contractility and blood pressure in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418:676-681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.076

- Saito R, So M, Motojima Y, et al. Activation of Nesfatin-1-Containing Neurones in the Hypothalamus and Brainstem by Peripheral Administration of Anorectic Hormones and Suppression of Feeding via Central Nesfatin-1 in Rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2016;28:10.1111/jne.12400. https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.12400

- Ozcan M, Gok ZB, Kacar E, Serhatlioglu I, Kelestimur H. Nesfatin-1 increases intracellular calcium concentration by protein kinase C activation in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2016;619:177-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2016.03.018

- Brailoiu GC, Dun SL, Brailoiu E, et al. Nesfatin-1: distribution and interaction with a G protein-coupled receptor in the rat brain. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5088-5094. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2007-0701

- Nakata M, Manaka K, Yamamoto S, Mori M, Yada T. Nesfatin-1 enhances glucose-induced insulin secretion by promoting Ca(2+) influx through L-type channels in mouse islet β-cells. Endocr J. 2011;58:305-313. https://doi.org/10.1507/endocrj.k11e-056

- Ayada C, Turgut G, Turgut S. The effect of Nesfatin-1 on heart L-type Ca²+ channel α1c subunit in rats subjected to chronic restraint stress. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2015;116:326-329. https://doi.org/10.4149/bll_2015_061

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2026 The author(s). This is an open-access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.