Abstract

Neuronutrient supplements are widely marketed as adjunctive treatments for neurological disorders, but their scientific validity is limited. This review highlights the disconnect between consumer-driven use and the lack of compelling clinical evidence. While a mechanistic possibility exists, the proliferation of these products risks undermining evidence-based neurology without standardized assessment frameworks.

Keywords: neuro-nutraceutical, neuronutrient, oxidative stress, dementia, marketing strategy, evidence-based medicine

Main Points

- A wide variety of neuro-nutraceuticals are available on the global market.

- Nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals are subject to the same ethical and scientific principles without exception.

- The claimed effects of neuro-nutraceuticals on neurological diseases are often based on low-quality evidence.

- Clinicians need to be familiar with these substances so that they can recognize the potential harms that may occur if their patients consume them on their own.

- It is scientifically rational to recommend avoiding any supplement unless a symptomatic deficiency is proven.

Introduction

Neuro-nutraceuticals are increasingly marketed for neurological health, yet their scientific validity remains limited. Despite plausible biological mechanisms, clinical evidence is fragmented, and consumer demand often outpaces regulatory and methodological rigor.1 This review addresses the gap between popularity and evidence, advocating for structured assessment to protect the integrity of evidence-based neurology.

Terminology

The term “Functional Food” refers to nutritional products specifically formulated to achieve targeted health outcomes, such as disease treatment, prevention, or overall health improvement, by introducing new ingredients or modifying the structure and quantity of existing ones. These products, also known as “Health Functional Foods (HFF)”, are available in forms such as tablets, capsules, powders, granules, and syrups. They are known by different names worldwide: “Dietary Supplements” in the U.S., “FOSHU” (Food for Specific Health Use) in Japan, and “Food Supplements” in Europe. More than 50,000 HFF products claim neurological benefits. In 1989, Dr. Stephen L. DeFelice coined the term “Nutraceutical”, merging “nutrition” and “pharmaceutical,” to describe a subset of HFFs.2 Today, this category includes around 60 subgroups, with approximately 1,000 compounds recognized for their medical importance. In this article, we refer to nutraceuticals developed specifically for the treatment of neurological diseases as neuro-nutraceuticals.

Knowledge Generation in Clinical Nutrition Science

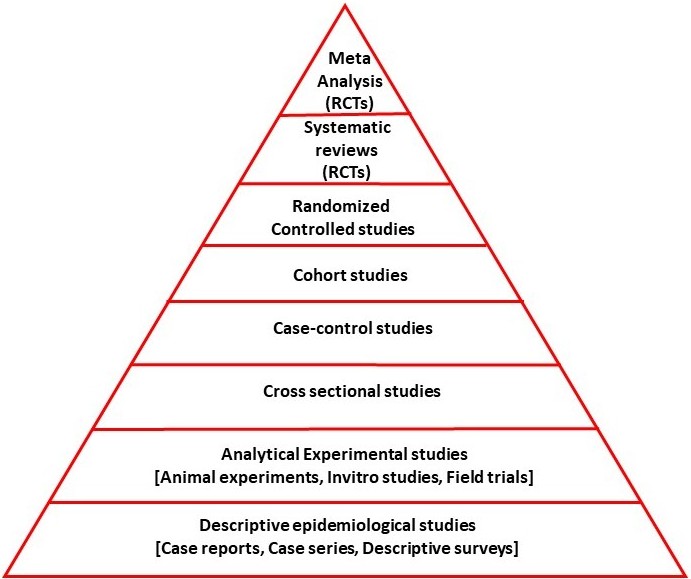

Evidence that a nutritional substance can positively impact a disease generally stems from five hierarchical sources: “Concept formation”, “Research into the relationship between the nutraceutical and the disease prevalence in the normal populations”, “Studies of the nutraceutical’s effects in the diseased population”, “Uncontrolled efficacy studies”, and “randomized controlled trials (RCT)” (Figure 1).3,4

Emergence of hypotheses/opinions regarding the effects of a nutraceutical: The notion that a nutraceutical may have an effect on a disease typically stems from animal or in vitro experimental studies, case studies, case series, or descriptive epidemiological surveys. This means that a causal mechanism by which the nutraceutical may have an effect on the disease must be hypothesized. This opinion/hypothesis can be expressed in scientific articles, such as expert opinions, editorials, or opinion articles on the subject.

Epidemiological studies investigating the change in disease frequency with nutraceutical consumption in the normal population: These analytical studies are observational in nature and may be cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort studies. They may be retrospective or prospective in design. Some are not hypothesis-driven and are based on new findings identified in the study. Various methods have been used to investigate the relationship between dietary intake and disease prevalence. The first involves determining the amount of a particular food present in the diet and analyzing its correlation with the frequency or prevalence of a disease. This can help identify whether higher or lower consumption of a food is associated with greater or lesser risk. The second method includes measuring specific biomarkers or molecules found in the food, sometimes after its dietary amount is determined, and evaluating their levels in biological samples such as serum, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or tissues. The relationship between these measured levels and disease frequency is then examined to understand potential physiological mechanisms. The third approach is to evaluate the effect of supplementation. Researchers investigate whether individuals who consume the food intentionally as a supplement show differences in disease prevalence compared to those who do not. Finally, the fourth method involves manipulating the dietary intake of the food and observing its effects on disease epidemiology. This may include increasing, decreasing, or eliminating the food from the diet and studying the subsequent changes in disease incidence.

For example, a researcher exploring chocolate’s effect on dementia may first categorize individuals by their chocolate intake (e.g., none, low, high consumption). Then, using cohort, cross-sectional, case-control with prospective or retrospective designs, they could examine the correlation between chocolate consumption and dementia incidence.5 They might also measure levels of a compound like “Flavan-3-ol” (found in cocoa) in the blood and analyze its association with dementia rates.6 Furthermore, investigating dementia frequency among individuals who consume chocolate as a targeted supplement could offer additional insights.7 Finally, observing changes in dementia incidence following alterations in chocolate consumption, such as beginning, stopping, or adjusting the amount, can help reveal causal relationships.8

Epidemiological studies investigating the relationship between disease course and characteristics and nutraceutical consumption:

These are prospective or retrospective studies, either cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort, involving individuals with the disease. In other words, they examine the effects of increasing or decreasing dietary intake, adjusting the amount, or adding supplements of a given nutrient on the severity and course of the disease. In this context, studies are conducted on individuals with the disease. For example, studies investigating the effects of increasing or decreasing daily chocolate consumption or consuming chocolate-containing supplements on the course of Alzheimer’s disease fall into this category.

Uncontrolled efficacy studies: Beyond the previous two categories, such as cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies, observational studies are non-randomized studies that test the effectiveness of a nutraceutical without a suitable control group. These studies examine the clinical efficacy of a nutraceutical consumed in a proof-of-concept manner and its effects on various surrogate markers, such as biomarker levels and neuroimaging. They differ from the previous group in their prospective design and the inclusion of participants based on established criteria rather than field recruitment. For example, this group includes a prospective study in which a pre-defined number (sample size) of Alzheimer’s disease patients are selected according to specific pre-defined study-specific criteria and are required to consume a specified amount of chocolate to assess its effects and side effects.

Randomized controlled trials: If above-mentioned studies determine the appropriate dosage and tolerability of side effects, the next step is RCTs. If RCTs meet quality standards and yield positive clinical results, the nutraceutical substance may be recommended for therapeutic use.

Differences Between Drug and Nutraceutical Supplement Studies and Approvals

Drugs and dietary supplements including any nutraceuticals differ significantly in their development, regulatory oversight, and scientific validation (Table 1).

| Table 1. Research and Development Process | ||

| Phase | Drugs | Supplements |

| Preclinical Studies | Animal and cell-based safety and efficacy tests | Often minimal or absent |

| Clinical Trials | Phases I–IV with thousands of participants | Usually small-scale, Phase I–II only |

| Efficacy Evidence | Proven via RCTs | Often based on observational or anecdotal data |

| Safety Monitoring | Long-term pharmacovigilance systems | Limited tracking, often reliant on manufacturers |

Legal Definition and Regulatory Bodies: Drugs are designed to diagnose, treat, or prevent diseases. They undergo rigorous approval processes by agencies like the FDA (U.S.), EMA (Europe) and Ministry of Health (Türkiye). Nutraceuticals as supplements are intended not only to support general health but also to treat diseases. In the U.S., they are regulated as foods under “the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA)”, with limited pre-market oversight. The system is similar in Türkiye, where a similar approval is given by the Ministry of Agriculture for nutraceuticals to be marketed, that is, sold.

Approval and Marketing: Pharmaceutical agents are subject to rigorous regulatory assessments that necessitates comprehensive data regarding their safety, efficacy, and manufacturing consistency. This approval process, typically overseen by agencies, such as the FDA, EMA and Turkish Ministry of Health, requires longitudinal, phase-based clinical trials and strict adherence to quality control standards. Consequently, drug development timelines can span decades and incur substantial financial costs. In contrast, nutraceutical products are generally exempt from regulatory approval before launch. They are classified under food legislation, and while manufacturers are responsible for ensuring product safety, they are not mandated to provide evidence of therapeutic efficacy prior to market introduction. This discrepancy reflects the differing regulatory paradigms and evidence expectations assigned to compounds intended for consumer health, which differ from those designated for clinical intervention.9

Scientific and Clinical Reliability: Drugs are backed by high-level evidence and undergo peer-reviewed trials. Supplements often rely on lower-tier evidence, and their claims may not be scientifically validated.

The Antioxidant Paradox: An example of the never-ending disparity and struggle between the generation of scientific knowledge and the promotional mechanisms of the food industry

The term “ Antioxidant paradox” was coined by Professor Barry Halliwell.10,11 This concept offers a compelling lens through which to examine the tension between scientific understanding of neuronutraceutical supplementation and the marketing practices of the food industry. One example Halliwell gave in his original article was that people with diets rich in fruits and vegetables have a decreased chance of developing cancer and an increase in the concentration of β-carotene in the blood. Supplements of β-carotene, however, do not have an anti-cancer effect, but rather the opposite in smokers.10,12 The antioxidant paradox is the notion that numerous studies have shown that an antioxidant-rich diet positively impacts health, primarily by protecting against atherosclerosis-related vascular diseases such as cancer and stroke/coronary artery disease.13,14 However, the findings of numerous randomized controlled trials consistently demonstrated that antioxidant supplementation does not confer measurable neurological or general health benefits. In fact, high-frequency supplementation has been associated with increased mortality in certain populations, particularly older adults. In brief, the antioxidant paradox refers to the fact that dietary antioxidants work, while supplemental antioxidants do not. Thus, the antioxidant paradox reinforces the idea that whole-food-based dietary interventions are preferable to isolated supplement strategies for both vascular and cognitive protection.

The discrepancy between the benefits of antioxidant-rich diets and the limited efficacy of antioxidant supplements reflects the intricate balance of human redox biology. A certain level of oxidative stress is thought to be necessary for life, and at low levels, it is thought to be paradoxically beneficial as an adaptive defense system. Improvement in general health through calorie restriction and increased regular physical activity has been linked to this mechanism. In these two strategies, ROS production increases in mitochondria. The effects of pro-oxidant molecules such as hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrite, nitric oxide, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen, hydroperoxyl radical, and lipid peroxide radical are balanced in the body by endogenous defense mechanisms such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione, uric acid, and thioreductase, as well as dietary intake of vitamins A, C, E, polyphenols and their related compounds, and minerals such as selenium.15 The balance between oxidant and antioxidant activity is finely tuned in the body. If this capacity is not measured accurately and supplemented accordingly, a critical imbalance can develop. However, measuring the antioxidant/prooxidant balance is complex because serum levels are not always useful. Tissue levels are more important, but there are differences between tissues. This complexity does not apply to antioxidant-rich whole foods. While these foods provide a good replacement because they contain a variety of bioactive compounds, including antioxidants that act synergistically to support cellular health, isolated supplements often fail to mimic this complexity. Furthermore, antioxidants found in natural sources often exhibit superior bioavailability and enhance resilience by triggering endogenous defense mechanisms through adaptive hormetic signaling. Adaptive hormetic signaling refers to the biological process by which low-level exposure to a stressor, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), calorie restriction, or phytochemicals, triggers beneficial cellular responses that enhance resilience, repair, and longevity. Conversely, high-dose supplementation can override these subtle regulatory processes, potentially causing reductive stress or interfering with critical ROS-mediated signaling pathways, leading to negative consequences. This highlights that nutrition is not simply about quantity but also a nuanced orchestration of biochemical interactions. It is an orchestra that supplementation alone can rarely manage with skill. The Antioxidant Paradox stems from the contribution of dosage and preparation, or collateral pathways, not the effect itself, but the diet’s high fruit and vegetable content.16 However, the number of products on the market claiming antioxidant effects without scientific support is quite high.

Neuro-nutraceutical use and Disease: Misconceptions that keep circulating

Under this heading, I list the facts and myths that I have identified based on the literature and my own experiences and observations, which have become long-standing and seem to be quite difficult to overcome.

Myth: Neuro-nutraceuticals have no effects or side effects. They are placebos.

The definition of neuro-nutraceutical is vague, but they are not placebos and certainly not harmless compounds. Excluding them from medical education and practice is a flawed policy. Public and commercial media are highly interested in the topic. Marketing touts miraculous effects while concealing side effects.17 Claiming there is no scientific evidence is useless. This does not protect people or patients. Doctors need to be knowledgeable about nutrition and able to answer patients’ questions. “I’m not interested!” is not an option.

Myth: Because neuro-nutraceuticals are food supplements, they are not subject to the same ethical and scientific rules as drugs.

The assumption that nutraceuticals, as dietary supplements, are exempt from the ethical and scientific standards applied to pharmaceuticals is unfounded. In practice, their approval and application must conform to the established hierarchy of evidence that informs drug therapies. This hierarchy encompasses four tiers: Class I evidence, the most robust, requires at least one RCT conducted in a representative population and assessed using masked, objective outcome measures. Class II evidence also involves RCTs, but has certain methodological limitations. Class III evidence is based on non-randomized controlled trials and supports only tentative recommendations. Class IV evidence, comprising expert opinions, consensus statements, and clinical guidelines, is deemed insufficient for contemporary therapeutic guidance.3 Treating nutraceuticals outside this rigorous evaluation framework compromises both scientific integrity and clinical confidence.

Fact: The effects of neuro-nutraceuticals in neurological diseases are generally based on third- or fourth-tier evidence.

While the same hierarchy of evidence applies to clinical neuronutrition as to pharmaceuticals, large-scale randomized trials are still rare, particularly outside of intensive care settings. Guidance is typically derived from meta-analyses or systematic reviews of small-scale trials. However, such comprehensive syntheses are uncommon in the nutraceutical field, where recommendations primarily based on observational studies and expert consensus.4 To justify neuro-nutraceutical use with the necessary rigor and confidence, we must adhere to the core principles of drug development and evaluation. At a minimum, evidence must demonstrate a plausible mechanism of action, supported by experimental data. Theoretical justification alone is insufficient. Furthermore, case-control and cohort studies suggesting that nutrient deficiency increases disease risk or that excess may reduce it should not, by themselves, be considered adequate to make treatment recommendations.

Fact: The impact of neuronutrient supplements on neurological diseases or global health is uncertain. Despite this scientific reality, market and product diversity are increasing exponentially.

The effectiveness of neuronutrient supplements in neurological diseases and global health remains scientifically ambiguous, despite an exponential growth in market and product diversity. Observational data alone are insufficient; at least prospective cohort studies must demonstrate that targeted supplementation or replacement of deficiencies leads to measurable biological increases in the absence of RCTs. For instance, although vitamin D deficiency is frequently observed in dementia patients, this association may reflect underlying lifestyle factors such as limited sun exposure, reduced mobility, and poor nutrition, rather than direct causation.18,19 This observation therefore contradicts the systemic nature of the condition. Moreover, randomized controlled trials have not demonstrated significant plasma level improvements with vitamin D administration, raising questions about tissue-level uptake and actual therapeutic benefit. In light of these not convincing enough RCT results20, current evidence does not support routine clinical recommendations for vitamin D supplementation (not equivalent to replacement) in patients with dementia.21

Fact: Nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals are subject to the same ethical and scientific rules without exception.

The therapeutic impact of neuronutrient supplements in neurological diseases remains marginal. Much of the literature supporting these products originates from non-peer-reviewed sources, rendering it largely inaccessible to clinical practitioners. Because these compounds are classified as dietary supplements or medical foods, they escape the scrutiny of regulatory bodies. When clinical evidence fails to meet second-tier standards, manufacturers often shift toward marketing strategies that circumvent rigorous drug approval pathways. Tramiprosate serves as a cautionary precedent: after Phase 3 RCTs failed to satisfy FDA benchmarks, the manufacturer abandoned its pursuit of prescription status.22,23 The compound resurfaced in commercial channels, where it now circulates without regulatory oversight.

Fact: Supplements shouldn’t be taken unless a deficiency is demonstrated.

A notable asymmetry exists between dietary modification and supplementation studies in neuronutrition. Enhancing antioxidant intake through whole-food diets has demonstrated consistent clinical benefits, while isolated antioxidant supplements have shown limited efficacy and, in some cases, negative results in RCTs. This reflects “the Antioxidant Paradox” noted above. Despite these findings, anti-oxidation-targeted neuro-nutraceuticals, particularly multivitamin blends, remain widely available in the commercial market. Clinical practice discourages such supplements in the absence of documented deficiencies, as supra-physiological dosing may pose risks. Conversely, when deficiencies manifest symptomatically, physiological-dose replacement to restore homeostasis is indicated. In summary, current evidence does not support recommending neuro-nutraceuticals for general use. However, clinicians must understand their pharmacological profiles to recognize potential harms in self-directed consumption.

Conclusion

Consequently, while neuronutraceuticals are widely marketed and increasingly consumed, their claimed neurological benefits are largely unsupported by robust evidence. Clinicians must remain vigilant and ethically consistent in their evaluation of these substances, recognizing that pharmacological and nutraceutical interventions adhere to the same principles of evidence-based practice. Given the documented risks associated with unregulated supplements and the prevalence of low-quality efficacy claims, it is clinically prudent to recommend against routine use in the absence of a demonstrable deficiency. This stance not only protects patients from potential harm but also strengthens the integrity of rational treatment decision-making.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Wal P, Aziz N, Dash B, Tyagi S, Vinod YR. Neuro-nutraceuticals: Insights of experimental evidences and molecular mechanism in neurodegenerative disorders. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2023;9(1):31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-023-00480-6

- Brower V. Nutraceuticals: poised for a healthy slice of the healthcare market? Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:728-731. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0898-728

- Wallace SS, Barak G, Truong G, Parker MW. Hierarchy of evidence within the medical literature. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12:745-750. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2022-006690

- Mann JI. Evidence-based nutrition: Does it differ from evidence-based medicine? Ann Med. 2010;42:475-486. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890.2010.506449

- Moreira A, Diógenes MJ, de Mendonça A, Lunet N, Barros H. Chocolate consumption is associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;53:85-93. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160142

- Socci V, Tempesta D, Desideri G, De Gennaro L, Ferrara M. Enhancing human cognition with cocoa flavonoids. Front Nutr. 2017;4:19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2017.00019

- Vyas CM, Manson JE, Sesso HD, et al. Effect of cocoa extract supplementation on cognitive function: results from the clinic subcohort of the COSMOS trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024;119:39-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.10.031

- Crichton GE, Elias MF, Alkerwi A. Chocolate intake is associated with better cognitive function: the maine-syracuse longitudinal study. Appetite. 2016;100:126-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.010

- Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:491-502. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2017.75

- Halliwell B. The antioxidant paradox. Lancet. 2000;355:1179-1180. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02075-4

- Gutteridge JM, Halliwell B. Reoxygenation injury and antioxidant protection: a tale of two paradoxes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;283:223-226. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(90)90635-c

- Rowe PM. Beta-carotene takes a collective beating. Lancet. 1996;347:249. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90413-4

- Li J, Lee DH, Hu J, et al. Dietary inflammatory potential and risk of cardiovascular disease among men and women in the U.S. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2181-2193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.535

- Giurranna E, Nencini F, Bettiol A, et al. Dietary antioxidants and natural compounds in preventing thrombosis and cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:11457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252111457

- Gulcin İ. Antioxidants: a comprehensive review. Arch Toxicol. 2025;99:1893-1997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-025-03997-2

- Duan M, Zhu Z, Pi H, Chen J, Cai J, Wu Y. mechanistic insights and analytical advances in food antioxidants: a comprehensive review of molecular pathways, detection technologies, and nutritional applications. Antioxidants (Basel). 2025;14:438. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14040438

- Verhagen H, Vos E, Francl S, Heinonen M, van Loveren H. Status of nutrition and health claims in Europe. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;501:6-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2010.04.012

- Duchaine CS, Talbot D, Nafti M, et al. Vitamin D status, cognitive decline and incident dementia: the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Can J Public Health. 2020;111:312-321. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-019-00290-5

- Gil Martínez V, Avedillo Salas A, Santander Ballestín S. Vitamin supplementation and dementia: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2022;14:1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051033

- Jia J, Hu J, Huo X, Miao R, Zhang Y, Ma F. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on cognitive function and blood Aβ-related biomarkers in older adults with alzheimer’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90:1347-1352. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-320199

- Manson JE, Crandall CJ, Rossouw JE, et al. The women’s health initiative randomized trials and clinical practice: a review. JAMA. 2024;331:1748-1760. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.6542

- Aisen PS, Gauthier S, Ferris SH, et al. Tramiprosate in mild-to-moderate alzheimer’s disease - a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centre study (the Alphase Study). Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:102-111. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2011.20612

- Bouhuwaish A. Efficacy and safety of tramiprosate in alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2024;20:e084063. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.084063

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2026 The author(s). This is an open-access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.