Abstract

Background: To investigate the changes in body composition and treatment outcomes in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer who receive regular and continuous nutritional counseling during radiotherapy.

Methods: Medical records of 26 patients who received regular weekly nutritional and dietary counseling during radiotherapy were retrospectively analyzed. Anthropometric parameters—including weight (kg), body mass index (BMI), muscle mass (MM, kg), fat-free mass (FFM, kg), body fat mass (BFM, kg), visceral fat rate (VFR), and basal metabolic rate (BMR, kcal/day)—were measured at baseline and at the end of radiotherapy by a registered dietitian using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). Measurements were compared from the start to the end of radiotherapy. Survival analysis was conducted using Kaplan-Meier curves.

Results: By week 5, weight decreased by 7.3% and BMI by 6.2%. Losses in MM and FFM were also significant (MM: 4.7%, FFM: 4.4%), with the most significant decrease observed in VFR (-8.0% at week 5). BMR decreased by 4.7%, aligning with overall weight and muscle mass loss. Severe weight loss (≥5%) was associated with higher rates of problems related to oral intake, including taste changes, nausea/vomiting, dental issues, low ONS tolerance and adherence, and aspiration. Median follow-up was 8 months (range, 6 to 42 months). Two-year local control (LC) and progression-free survival (PFS) were 56.2% and 54.9%, respectively. Survival rates were significantly lower in patients with severe weight loss (LC, p=0.041; PFS, p=0.027).

Conclusion: Radiotherapy results in a decrease in weight, muscle mass, and fat over weeks. Survival outcomes are significantly worse in patients who experience severe weight loss. Since radiotherapy itself is a risk factor for malnutrition, early, regular, and proactive nutritional intervention may be recommended to prevent and manage malnutrition and maintain function in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy.

Keywords: body composition, regular dietary counseling, head and neck cancer, malnutrition, radiotherapy

Main Points

- Nutrition is critically important for patients with head and neck cancer because it dramatically impacts treatment outcomes.

- Radiotherapy results in a decrease in weight, muscle mass, and fat over weeks. Survival outcomes are significantly worse in patients who experience severe weight loss.

- Dietary counseling may enhance nutritional quality and patient awareness, but it cannot fully prevent treatment-related weight loss, as therapy-induced toxicities remain a predominant factor.

- Future clinical practice and research should prioritize multidisciplinary interventions that combine dietary counseling, physical activity, and metabolic monitoring to optimize body composition.

Introduction

Nutrition is critically important for patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) because it significantly impacts both treatment tolerance, outcomes, and quality of life.1,2 In this patient group, comorbidities, tumor location, stage, and cancer treatments such as surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy can increase the risk of malnutrition.3-5 A major challenge in managing these patients is unintentional weight loss, which is often present at diagnosis and may worsen during treatment. A decline in nutritional status results in reduced treatment adherence and poorer cancer outcomes.6-10

Nutritional counseling throughout radiotherapy is recognized as an essential component of care for patients with head and neck cancer (HNC), given the rapid and dynamic changes in nutritional status these patients experience during treatment.9,11-14 The risk of malnutrition increases as radiotherapy advances, mainly due to side effects such as mucositis, dysphagia, and taste changes, which can lead to significant weekly declines in dietary intake and nutritional status.3-5,11-14 Regular, personalized counseling sessions provided by trained dietitians have been shown to improve nutritional care and outcomes for patients at risk of malnutrition.15

Nevertheless, despite widespread recognition of these risks, significant gaps remain in the prevention and management of malnutrition among HNC patients. Recent roadmap statements and systematic reviews emphasize the urgent need for data-driven studies that evaluate practical aspects of nutritional interventions, including the optimal frequency, timing, and specific effects of personalized counseling and monitoring during radiotherapy.16 The current literature also highlights barriers such as limited access to professional nutrition care and unclear guidance on which nutritional strategies most effectively preserve body composition and support favorable treatment outcomes for this patient group.15,16

Body composition changes during radiotherapy in HNC patients are characterized by significant losses in lean body mass, skeletal muscle, fat-free mass, and body fat.17 Severe loss of body composition during radiotherapy increases the risk of postoperative complications, reduces quality of life, worsens functional outcomes, and may decrease survival rates.18Therefore, regular assessment and intervention focused on maintaining healthy body composition may improve outcomes in HNC patients receiving radiotherapy.17

Systemic inflammatory markers such as NLR (Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio), PLR (Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio), and SII (Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index) are increasingly used to evaluate the systemic inflammatory response and predict outcomes in HNC patients undergoing radiotherapy.19,20 Higher levels of these markers are also associated with an increased risk of severe side effects such as mucositis and impaired nutritional status, which may further lead to unfavorable outcomes.20,21

The present study aims to prospectively assess week-by-week changes in body composition and systemic inflammatory markers in patients with HNC who receive regular, scheduled nutritional counseling during radiotherapy. To our knowledge, few studies have examined this approach in routine clinical practice.14 Therefore, our research aims to enhance understanding of how structured nutritional advice affects both nutritional and oncologic outcomes during radiotherapy in this high-risk group.

Materials and Methods

Study population and design

This retrospective study analyzed 26 patients who completed regular weekly nutritional counseling and intervention by a registered dietitian during radiotherapy. Seventy-two patients were initially eligible; only those who completed the intervention for all weeks were included in the final analysis, thereby minimizing loss to follow-up and selection bias. All patients continued regular follow-up in the head and neck cancer outpatient clinic in our radiotherapy center; individual demographics, disease, and treatment characteristics are provided in Table 1.

| Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population at the initiation of radiotherapy (n = 26) | |

|

|

|

| Tumor location | |

| Larynx |

|

| Nasopharynx |

|

| Oral cavity |

|

| Sinonasal |

|

| Oropharyngeal |

|

| Salivary gland |

|

| Gender | |

| Male |

|

| Female |

|

|

|

|

| Age (years) |

|

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy

Radiotherapy treatment planning used Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy (VMAT, Monaco Treatment Planning System v5.11), delivered with a linear accelerator (Elekta Synergy, 6 MV photons), with a median radiotherapy dose of 60 Gy. All but two patients received concurrent weekly cisplatin (40 mg/m²) according to standard protocols.

Nutritional intervention

A registered dietitian provided standardized, face-to-face nutritional counseling sessions (~30 min) for each patient weekly during radiotherapy. These sessions documented current dietary intake, food records, socioeconomic status, and nutrition-related toxicities. Adherence to dietary recommendations was monitored each week. The Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) was performed at both baseline and the end of treatment.22 A weekly dietary recall was collected before each counseling session. During weekly interviews, patients’ adherence to the prescribed counseling was monitored based on the previous week. Daily energy requirements were calculated using the Harris-Benedict formula and protein intake (1.2 g/kg/day), and oral nutrition supplements (ONS) were provided to patients who did not meet targets.23,24 ONS intolerance was defined as the inability to meet the daily recommended intake. In our study, physical activity status was assessed through direct interview at baseline during dietitian counseling sessions. Patients were asked about their typical daily routines, work status, and engagement in structured exercise. Based on these self-reports, all patients were classified as either inactive or engaged only in light physical activities. The energy and protein requirements were calculated using the sedentary (inactive) or light activity factors since no patient reported regular activity exceeding these levels.

Measurement and data collection

Anthropometric and body composition parameters—including weight (kg), body mass index (BMI), muscle mass (MM, kg), fat-free mass (FFM, kg), body fat mass (BFM, kg), visceral fat rate (VFR), and basal metabolic rate (BMR, kcal/day)—were measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) with the TANITA BC-420MA device. The Densi GL-150 automatic system was used for height (cm) and weight (kg).

The mean and SD of inflammatory parameters, including NLR, PLR, and SII, were calculated.25-27 The parameters collected at the beginning and end of radiotherapy were compared.

Side-effect evaluation was performed by radiation oncologists, and the Common Toxicity Criteria v5.0 was used to assess the severity of various side effects.28 Standard medications, like antiemetics and analgesics, mouthwash, and, in case of antibiotics, were administered for pain and nausea/vomiting caused by mucositis and painful swallowing.

Statistical analyses and visualization

Inclusion criteria limit the analysis to patients who completed all intervention weeks, reducing information bias. Outcome assessment included weekly monitoring and standardized data collection to optimize reliability. Repeated measures data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Mean ± SD trends for each variable were plotted to assess intra-individual changes over time. Weekly percentage changes were derived as:

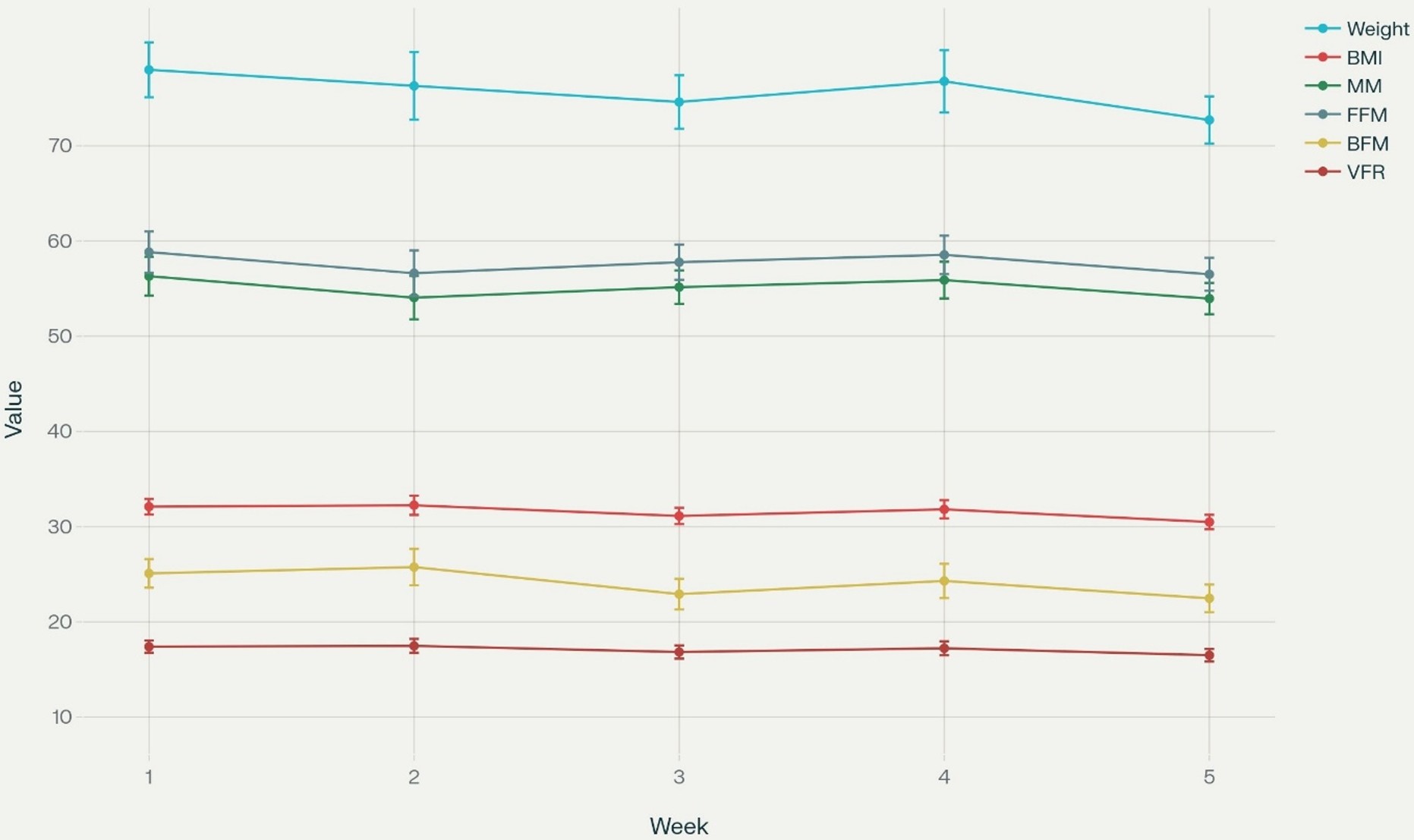

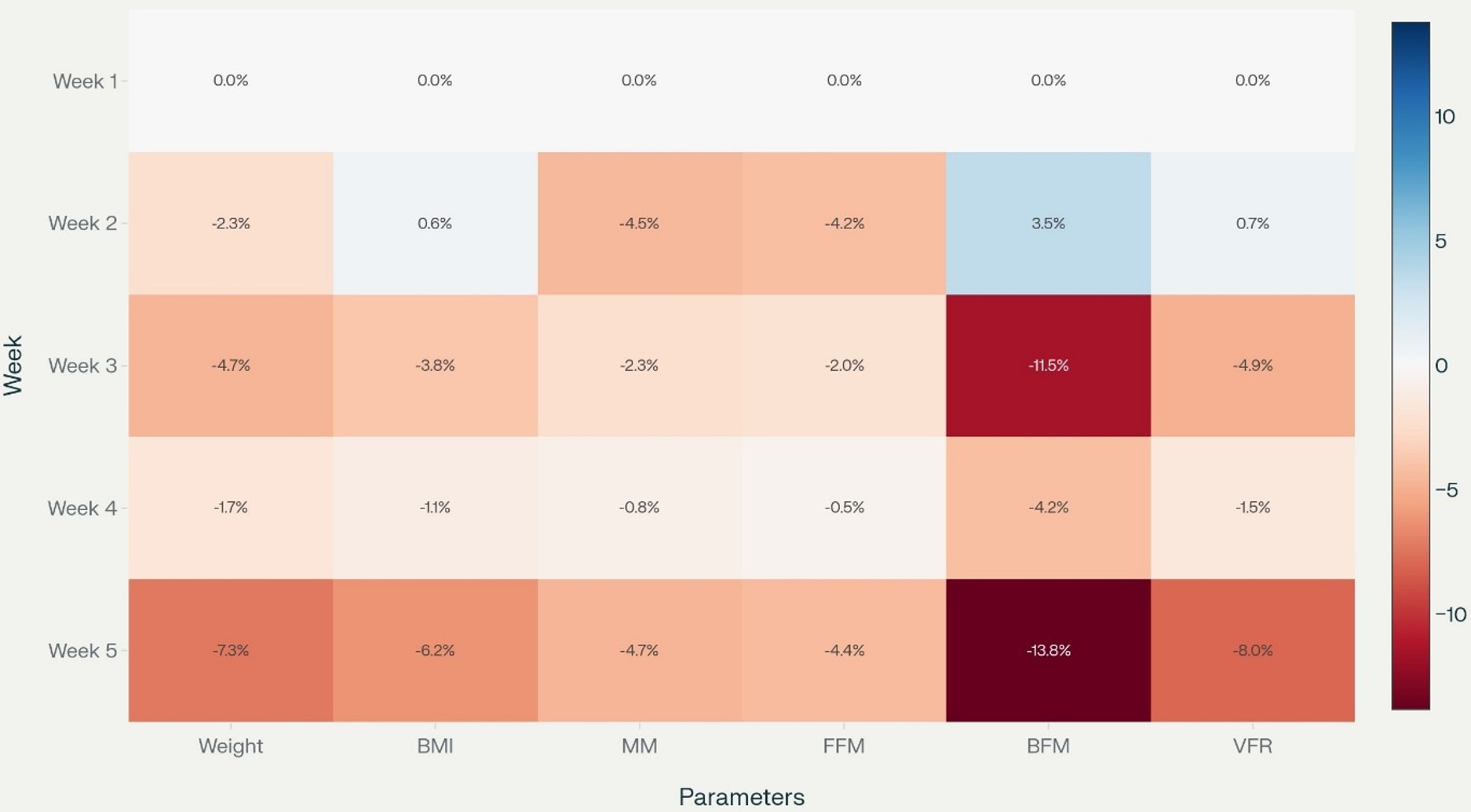

Significance testing (e.g., repeated-measures ANOVA or the Friedman test) was performed as appropriate for continuous, repeated-measures data. For the longitudinal trend analysis (Figure 1), mean values with standard deviation (SD) for each parameter were plotted across five consecutive weeks. Weekly percentage changes in body composition metrics were calculated relative to baseline (week 1) and visualized as a heatmap (Figure 2) to illustrate the temporal progression and magnitude of change for each parameter. Figure 1 and Figure 2 were generated with coding and analytic assistance using Python (version 3.x) with packages including pandas, matplotlib, and seaborn in Perplexity AI (Pro version, September 2025), an artificial intelligence platform, using user-supplied data, prompts, and post-analysis parameter review. The code and figure design were reviewed and finalized by the authors. The correlation analysis was performed using Spearman’s correlation.

Group comparisons, outcome analyses, and survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier curves. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as local or distant failure, whereas local control (LC) was defined as local and/or regional progression without any systemic progression. Survival outcomes were calculated from the beginning of radiotherapy till the last follow-up or death. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All patients completed radiotherapy, and no disease progression was observed during and at the end of concurrent treatment. Patients began radiotherapy after losing a mean of 12 kg following surgery. The mean weight loss was 5.27±3.89 kg (7.01%,1.36% to 18.75%). Weekly changes of the study measurements during radiotherapy are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Weight decreased gradually over the weeks, with a minor increase in week 4, followed by the lowest value in week 5. BMI closely mirrored the weight trajectory, declining steadily except for a slight increase in week 4, then reaching the lowest point in week 5. Both MM and FFM followed a similar pattern—reduction from week 1 to week 3, a modest rebound in week 4, and then another decline by week 5. VFR was fairly stable, with only slight fluctuations and a subtle downward trend, and BMR tracked overall body composition trends with minor changes week to week, reflecting the combined influence of the other parameters.

| BMI: body mass index; MM: muscle mass; FFM: fat-free mass; BFM: body fat mass; VFR: visceral fat rate; BMR: basal metabolic rate. | |||||||

| Table 2. Weekly changes in body composition and metabolic parameters during radiotherapy (mean ± standard deviation, n = 26) | |||||||

| Week |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The heatmap shows the percentage change in weekly body composition and metabolic variables relative to baseline (week 1) for patients undergoing radiotherapy (Figure 2). There is a progressive decline in almost all parameters except for a transient increase in BFM in week 2. By week 5, nearly all measures show meaningful reductions from baseline, indicating a cumulative loss in both fat and lean tissue. Both weight and BMI decrease steadily, with weight dropping by -7.3% and BMI by -6.2% by week 5. Losses in MM and FFM are also significant (MM: -4.7%; FFM: -4.4% by week 5), with the largest decrease observed in VFR (-8.0% by week 5). BMR decreases by -4.7% in week 5, matching the overall weight loss and MM. BFM is unique in showing a transient increase (+3.5%) in week 2. From week 3 onward, there is a sharp decline, reaching -13.8% in week 5.

The differences in body composition and inflammatory markers from the start to the end of radiotherapy were statistically significant (Table 3). The mean NLR, PLR, and SI were significantly high at the end of radiotherapy (p < 0.0001). No significant correlation was found between the increase in inflammatory factors (NLR, PLR, SII) during radiotherapy and the percentage of weight loss in patients (ΔNLR and % weight loss: Spearman’s rho ≈ 0.07, p = 0.76, ΔPLR and % weight loss: Spearman’s rho ≈ 0.04, p = 0.84, ΔSII and % weight loss: Spearman’s rho ≈ -0.19, p = 0.36).

| Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation at the beginning and end of radiotherapy. P-values indicate the statistical significance of differences between time points using paired tests. RT: radiotherapy; BMI: body mass index; MM: muscle mass; FFM: fat-free mass; BFM: body fat mass; BMR: basal metabolic rate. | |||

| Table 3. Pre- and post-radiotherapy values of body composition and inflammatory markers in the overall study cohort (n = 26) | |||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

| Weight (kg) |

|

|

|

| BMI (kg/m2) |

|

|

|

| MM (kg) |

|

|

|

| FFM (kg) |

|

|

|

| BFM (kg) |

|

|

|

| VFM (kg) |

|

|

|

| BMR (kcal) |

|

|

|

| NLR |

|

|

|

| PLR |

|

|

|

| SII |

|

|

|

The most significant ≥ grade 2 toxicities that could affect food and calorie intake included dysphagia (n = 20), nausea/vomiting (n = 11), and taste alterations (n = 10). Aspiration and dental prosthesis issues occur more frequently in patients with severe weight loss. Low ONS tolerance and adherence were frequently observed (n = 18) due to depression, taste intolerance, stomach fullness/early satiety, nausea, and dislike of the tastes of ONS (Table 4).

| Values represent the percentage of patients in each group who experienced the listed side effect during the study period. Mild-moderate weight loss is defined as a <5% reduction from baseline body weight, and severe weight loss as a ≥5% reduction. | ||

| Table 4. Frequency of side effects contributing to weight loss, stratified by mild-moderate (<5%) and severe (≥5%) weight loss groups (n=26). | ||

| Cause |

|

|

| Pain and dysphagia |

|

|

| Xerostomia |

|

|

| Smell intolerance |

|

|

| Appetite loss |

|

|

| Fullness/early satiety |

|

|

| Taste alteration |

|

|

| Nausea/vomiting |

|

|

| Dental prosthesis problems |

|

|

| Aspiration |

|

|

| ONS intolerance |

|

|

Four patients had local and/or distant progression at the time of analysis. Median follow-up was 8 months (range, 6 to 42 months). Two-year LC and PFS rates were 56.2% and 54.9%, respectively (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Patients with severe weight loss showed lower progression-free survival at the end of the follow-up (LC, p = 0.041; PFS, p = 0.027).

Discussion

There are limited studies on how frequent and consistent dietitian supervision and personalized counseling affect body composition and related clinical outcomes in head and neck cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. Key strengths of our study include providing weekly, face-to-face dietary counseling for all patients throughout radiotherapy, along with the systematic assessment of body composition parameters. This approach may highlight the importance of evaluating body composition rather than relying solely on body weight, thereby providing clinically relevant insights into the mechanisms underlying malnutrition and its potential impact on patient outcomes.16,29

During radiotherapy, the frequency and intensity of side effects increase as cumulative radiation doses accumulate week by week. In our study, the most significant decrease occurred in the last week compared with the first. This indicated clinically significant weight loss, and this information was correlated with the dose-dependent side effect. The most significant decrease was observed in VFR. BMR decline paralleled the overall loss of weight and muscle mass, which may impair physical function and recovery potential.

The study measures showed a temporary increase in weeks 3 and 4. This might indicate a recovery in this period. Between weeks 4 and 5, all variables decreased sharply, especially VFR and weight. Changing directions may highlight the dynamic nature of these measurements and may indicate the response to intervention. The positive period in weeks 3 and 4 may suggest partial stabilization, as the most significant declines occurred in weeks 4 and 5 for most variables, possibly indicating a cumulative effect of radiation therapy. BFM is showing a transient increase in week 2, possibly due to fluid shifts or measurement variability. The transient increase in body fat mass (BFM) observed in week 2 may likely reflect short-term physiological changes rather than true fat gain.30 Radiation therapy and nutritional interventions can cause temporary fluid shifts—such as edema or changes in hydration status—which may be detected by bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) as an elevation in measured fat mass. Additionally, measurement variability may impact hydration and body composition readings, especially early in treatment. Therefore, this temporary BFM increase may reflect a short-lived change in fluid balance rather than a sustained accumulation of body fat.

From week 3 onward, there is a sharp decline, reaching week 5, indicating substantial fat loss. Only BMI and VFR display slight positive changes in week 2, which are short-lived and followed by further declines. The VFR remains almost unchanged in the early weeks, with minor increases, but decreases notably in week 5. This may suggest that not only subcutaneous fat, but also visceral fat was lost over the course of radiotherapy.31 A decline in basal metabolic rate may be associated with muscle mass loss, as muscle tissue is metabolically active.32,33 Skeletal muscle consumes the highest amount of energy among organ systems, and BMR reduction is associated with sarcopenia and muscle wasting.32

All three biomarkers (NLR, PLR, SII) increased by more than 2-fold during radiotherapy. No significant link was found between changes in inflammatory markers and body weight loss in the patient group. Since no disease progression was observed at the end of radiotherapy, this may suggest increased immune-inflammatory activation due to unavoidable cumulative side effects. These effects, like mucositis and dysphagia, may lead to catabolic stress related to muscle degradation and cachexia, which may be linked to inflammation.

Table 4 summarizes the main causes of weight loss in cancer patients, comparing those with <5% versus ≥5% weight loss, and presents the frequency (number and percentage) of each cause within both groups. Dysphagia pain is the most common reason in both groups, affecting more than 75% of patients with both <5% and ≥5% weight loss. Patients were advised to have a dental examination at the beginning of treatment to assess oral health. Despite that, dental issues, especially prosthesis-related problems, were among the major eating difficulties. Low ONS tolerance and adherence may be essential in preventing severe weight loss in this population. These findings highlight which side effects are most strongly associated with more significant weight loss and provide targets for nutritional interventions in cancer patients. Although prescribed based on dietary habits and taste preferences, ONS demonstrated notable low tolerance issues, often due to treatment-related side effects or declining tolerance over time.

In the survival analysis, both local control and progression-free survival were better in patients who had less weight loss. As mentioned previously, a body weight change of more than 5% during radiotherapy may be critical for survival outcomes.11 The weight loss due to cumulative side effects cannot be completely prevented for head and neck cancer patients in radiotherapy. Hence, we may say that it is better to start nutritional assessment and intervention at the beginning of radiotherapy, before the visible changes start. Patients may also receive dietary counseling during the postoperative period before radiotherapy. Dietary counseling may also be requested by cancer patients.34

Previous studies consistently identified weight loss as an independent prognostic indicator of survival in patients with HNC, highlighting its significant impact beyond traditional clinicopathological factors.8,18 However, later research showed that more comprehensive and multimodal approaches may be necessary to prevent significant weight loss.12,14 Therefore, in high-risk patients, proactive enteral nutrition strategies such as PEG or NG tube placement, the use of multimodal interventions including ONS and exercise, and closer monitoring may be needed.35-37 According to guidelines, patients who consume 75-80% of the recommended amount of ONS are considered to tolerate it well.36 Additionally, recent meta-analyses have confirmed that over 50% of patients experience critical weight loss, especially among those undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy, individuals with higher body mass index, and those with poor baseline performance status.38These findings emphasize the importance of systematically identifying high-risk subgroups and integrating proactive, personalized nutritional interventions into routine cancer care to reduce the negative effects of treatment-related weight loss on prognosis.

Although dietary support can enhance nutritional quality and patient awareness, it cannot fully prevent treatment-related weight loss, as therapy-induced toxicities remain a predominant factor. Nutritional counseling is undeniably valuable and should be regarded as an essential component of supportive care; however, maintaining body weight is rarely achievable during definitive chemoradiotherapy.39 While dietary interventions may improve oral intake, they are insufficient on their own to counter the profound metabolic catabolism induced by therapy. Preventing skeletal muscle depletion appears to require strategies beyond dietary modification. Therefore, integration of structured exercise programs with individualized nutritional support should be strongly recommended as part of a multimodal supportive care pathway.35,40 Future clinical practice and research should prioritize multidisciplinary interventions that combine dietary counseling, physical activity, and metabolic monitoring to optimize body composition, may reduce treatment-related toxicity, and ultimately improve survival outcomes in patients with HNC.

This study has several limitations. The retrospective, single-center design and the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, there was variability in the use of oral nutritional supplements (ONS) among participants, and the short median follow-up period may restrict the assessment of survival outcomes related to nutritional factors.

Conclusion

These results reflect the effects of radiotherapy on body composition, with notable decreases in weight, muscle mass, fat mass, and metabolic rate over 5 weeks. Survival outcomes are significantly worse in patients who experience severe weight loss. Since radiotherapy itself is a risk factor for malnutrition, weekly dietitian monitoring and counseling may help ensure timely assessment of body composition changes. They may help to decrease weight and muscle loss in HNC patients undergoing radiotherapy.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee for Research on Non-Drug and Medical Device Research of Marmara University (approval date 10.10.2024, number 10.2024).

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Martinovic D, Tokic D, Puizina Mladinic E, et al. Nutritional management of patients with head and neck cancer-a comprehensive review. Nutrients. 2023;15:1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081864

- Cardellini S, Deantoni CL, Paccagnella M, et al. The impact of nutritional intervention on quality of life and outcomes in patients with head and neck cancers undergoing chemoradiation. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1475930. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1475930

- Wang P, Lam Soh K, Geok Soh K, et al. Systematic review of malnutrition risk factors to identify nutritionally at-risk patients with head and neck cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2024;28:197-208. https://doi.org/10.1188/24.CJON.197-208

- Wallmander C, Bosaeus I, Silander E, et al. Malnutrition in patients with advanced head and neck cancer: Exploring the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) criteria, energy balance and health-related quality of life. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2025;66:332-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2025.01.049

- Atasoy BM, Özgen Z, Yüksek Kantaş Ö, et al. Interdisciplinary collaboration in management of nutrition during chemoradiotherapy in cancer patients: a pilot study. Marmara Med J. 2015;25:32-36. https://doi.org/10.5472/MMJ.2011.02072.1

- Ottosson S, Zackrisson B, Kjellén E, Nilsson P, Laurell G. Weight loss in patients with head and neck cancer during and after conventional and accelerated radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:711-718. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.731524

- Deng LH, Chi K, Zong Y, Li Y, Chen MG, Chen P. Malnutrition in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiotherapy: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2023;66:102387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2023.102387

- Capuano G, Grosso A, Gentile PC, et al. Influence of weight loss on outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing concomitant chemoradiotherapy. Head Neck. 2008;30:503-508. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20737

- Fange Gjelstad IM, Lyckander C, Høidalen A, et al. Impact of radiotherapy on body weight in head and neck cancer patients: a prospective study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2025;65:390-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2024.12.019

- Noronha V, Chawda A, Patil V, et al. Nutritional status and impact on outcomes of patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy: a pre-planned secondary analysis of a phase 3 randomized controlled trial. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2025;37:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43046-025-00305-y

- Atasoy BM, Bektaş Kayhan K, Demirel B, Akdeniz E. Mucositis-induced pain due to barrier dysfunction may have a direct effect on nutritional status and quality of life in head and neck cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. Turk J Oncol. 2020;35:40-46. https://doi.org/10.5505/tjo.2019.2161

- Orell H, Schwab U, Saarilahti K, Österlund P, Ravasco P, Mäkitie A. Nutritional counseling for head and neck cancer patients undergoing (Chemo) radiotherapy-a prospective randomized trial. Front Nutr. 2019;6:22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2019.00022

- Surwiłło-Snarska A, Kapała A, Szostak-Węgierek D. Assessment of the dietary intake changes in patients with head and neck cancer treated with radical radiotherapy. Nutrients. 2024;16:2093. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132093

- Zeidler J, Kutschan S, Dörfler J, Büntzel J, Huebner J. Impact of nutrition counseling on nutrition status in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radio- or radiochemotherapy: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024;281:2195-2209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08375-1

- Hopancı Bıçaklı D. Individualized nutritional management for cancer patients: a key component of treatment. Clin Sci Nutr. 2025;7:131-140. https://doi.org/10.62210/ClinSciNutr.2025.109

- Chen X, Beilman B, Gibbs HD, et al. Nutrition in head and neck cancer care: a roadmap and call for research. Lancet Oncol. 2025;26:e300-e310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(25)00087-7

- Ferrão B, Neves PM, Santos T, Capelas ML, Mäkitie A, Ravasco P. Body composition changes in patients with head and neck cancer underactive treatment: a scoping review. Nutr Diet Nutraceuticals. 2019;1:2-11. https://doi.org/10.31038/NDN.2019112

- Grossberg AJ, Chamchod S, Fuller CD, et al. Association of body composition with survival and locoregional control of radiotherapy-treated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:782-789. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6339

- Wang YT, Kuo LT, Weng HH, et al. Systemic immun e-inflammation index as a predictor for head and neck cancer prognosis: a meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:899518. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.899518

- Atasoy BM, Demirel B, Ekşi Özdaş FN, Devran B, Kılıç ZN, Gül D. The role of radiotherapy planning images in monitoring malnutrition and predicting prognosis in head and neck cancer patients: a pilot study. Radiat Oncol. 2025;20:70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-025-02645-4

- Huang X, Qin X, Huang W, Huang B. The predictive value of hematological inflammatory markers for severe oral mucositis in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma during intensity-modulated radiation therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Probl Cancer. 2024;51:101117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2024.101117

- Detsky AS, McLaughlin JR, Baker JP, et al. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1987;11:8-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/014860718701100108

- Roza AM, Shizgal HM. The Harris benedict equation reevaluated: resting energy requirements and the body cell mass. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;40:168-182. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/40.1.168

- Kok A, van der Lugt C, Leermakers-Vermeer MJ, de Roos NM, Speksnijder CM, de Bree R. Nutritional interventions in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy: current practice at the Dutch head and neck oncology centres. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2022;31:e13518. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13518

- Neutrophil-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) calculator. 2025. Available at: https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10305/neutrophil-lymphocyte-ratio-nlr-calculator.(Accessed on Sep 6, 2025).

- Platelet/Lymphocyte ratio calculator. 2025. Available at: https://calculator.academy/platelet-lymphocyte-ratio-calculator. (Accessed on Sep 6, 2025).

- COVID-19 and the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII). 2025. Available at: https://www.medcentral.com/calculators/infectious-disease/covid-19-and-the-systemic-immune-inflammation-index-sii. (Accessed on Sep 6, 2025).

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE): version 5.0. 2025. Available at: https://dctd.cancer.gov/research/ctep-trials/for-sites/adverse-events/ctcae-v5-5x7.pdf. (Accessed Sep 6, 2025).

- Hopanci Bicakli D, Ozkaya Akagunduz O, Meseri Dalak R, Esassolak M, Uslu R, Uyar M. The effects of compliance with nutritional counselling on body composition parameters in head and neck cancer patients under radiotherapy. J Nutr Metab. 2017;2017:8631945. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8631945

- Bell KE, Schmidt S, Pfeiffer A, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis overestimates fat-free mass in breast cancer patients undergoing treatment. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020;35:1029-1040. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncp.10438

- Chiloiro G, Cintoni M, Palombaro M, et al. Impact of body composition parameters on radiation therapy compliance in locally advanced rectal cancer: a retrospective observational analysis. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2024;47:100789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctro.2024.100789

- Maghbooli Z, Mozaffari S, Dehhaghi Y, et al. Correction: the lower basal metabolic rate is associated with increased risk of osteosarcopenia in postmenopausal women. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:323. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01913-9

- Carbone JW, McClung JP, Pasiakos SM. Skeletal muscle responses to negative energy balance: effects of dietary protein. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:119-126. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.111.001792

- Ece MN, Demirel B, Bayoğlu V, Uluköylü Mengüç M, Atasoy BM. Patient perspectives on dietitians’ role in nutrition management among cancer patients: implications for proactive care and communication. Clin Sci Nutr. 2024;6:160-167. https://doi.org/10.62210/ClinSciNutr.2024.99

- Bowen TS, Schuler G, Adams V. Skeletal muscle wasting in cachexia and sarcopenia: molecular pathophysiology and impact of exercise training. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015;6:197-207. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12043

- Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:11-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.07.015

- Atasoy BM, Yonal O, Demirel B, et al. The impact of early percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement on treatment completeness and nutritional status in locally advanced head and neck cancer patients receiving chemoradiotherapy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:275-282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-010-1477-7

- Zhang J, Fan Y, Pu M, Zhang J. Prevalence and risk factors for critical weight loss among patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2025;78:102960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2025.102960

- Krzywon A, Kotylak A, Cortez AJ, Mrochem-Kwarciak J, Składowski K, Rutkowski T. Influence of nutritional counseling on treatment results in patients with head and neck cancers. Nutrition. 2023;116:112187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2023.112187

- Maddocks M. Physical activity and exercise training in cancer patients. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;40:1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.09.027

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The author(s). This is an open-access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.